THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // BRAZIL (1985) |

Michel Palin on BRAZIL |  |

|

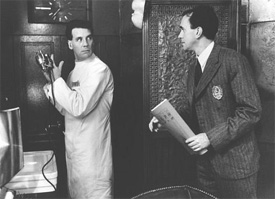

When did Terry first discuss brazil BRAZIL with you? Was it toward the end of TIME BANDITS or was it earlier than that? Palin: I can't actually remember the first time Terry discussed BRAZIL. I mean, we shot TIME BANDITS together I think in 1980. And BRAZIL was not filmed until late '83, early '84. He first probably talked to me at some depth maybe 18 months or a year after we'd done TIME BANDITS, possibly while we were shooting THE MEANING OF LIFE, which is of course we were working on together in late '82. Did he write the character of Jack specifically with you in mind? I don't think Terry did have me specifically in mind when he wrote Jack Lint. You'd have to ask him that. As far as I know, he'd written the script, he and Charles McKeown had written the script, and Arnon Milchan sort of, if you like, dangled before Terry the prospect of major stars including Robert De Niro, and De Niro was shown the script and he had a look-through and he said, of all the parts he'd like to do, Jack Lint was the one. So Terry said (this is Terry's story anyway), 'I'm sorry, my friend Mike is going to do that. You have to choose something else!' [LAUGHS] So that must be a rare example of De Niro being turned down! And I think that probably Terry once he'd written [it] may have thought of me as doing it because we worked quite closely on JABBERWOCKY and TIME BANDITS and I think he felt sort of, not exactly morally obliged just because we were good friends and had worked productively before, to offer me something on BRAZIL. But needless to say it was the part that De Niro had definitely wanted and De Niro was shifted off, so I ended up doing it. What intrigued you most about the character of Jack?

the scene that comes to mind is the office, where the two of you are discussing terrorism and so forth, and there's a little girl there playing ball that you do cootchie-coo with. I understand that wasn't the original way the scene was shot. I had a great problem with playing Jack which is I'd not really played a character like this before. It was also scheduled for the first day of shooting and it was about the most complicated scene in the film, which was really in retrospect a ridiculous bit of scheduling. You don't schedule your hardest scene involving complicated character dialogue and character playing until your cast have had time to get to know who they're playing and what they're playing. You schedule some gentler stuff. But there we were, crack in. I'd just spent a week in the Belfast Festival doing a one-man show so I was pretty exhausted, and we went in on day one and there was tremendous pressure to get the scene done, and get it done fast. Now, all sorts of things militated against that. I'd not worked with Jonathan before; Jonathan Pryce, he's quite an intense actor, and I'm a, you know, Python actor — we were intense for short periods but basically we rely on the love and the comfort and the easiness and the bouncing off lines one from another. Jonathan was searching for exactly how he should play his character, which was going to have to go through the entire film — he had another three months to go. And I was like, I felt the whole atmosphere was a bit tight and a bit tense and I wasn't particularly happy with my performance by the end of the day (two days actually we spent). We got it down and we'd done a couple of more scenes as well, and people were saying, 'Hey, we've got 12 pages of script under our belts. This is, this is great, what a start!' But of course once Terry looked at it and Julian the editor, I think they both felt that there was something lacking in the scene. It was a scene which relied a lot on knowing a complicated plot and being able to, in my case, spin out jargon very, very fast — you know, Buttles and Tuttles and all this, E/23 and a B/24 and all that sort of thing, which again was not easy to grasp. So after the two days we spent on it, I think it must have been November '83, I felt relieved that we'd done it, I thought we'd cracked it, [but] a little voice in the back of my mind said, 'you know this could be better.' So I was actually quite relieved when after a month or so, maybe longer, Terry said, 'You know, there are some problems, it might be worth it trying this scene again.' And after I got over the feelings of hurt pride — couldn't get it right the first time — I realized yes, well there were things wrong, and maybe we'd be able to improve on it. We talked about it, and between us we came to the conclusion that the great thing about Jack is that he is a family man, that he is a personification of the good citizen. And that there was no real indication of that in the first scene — it was just between the two of them. And if we could have some elements of family life in it, then that would make it all the more dark, sort of playing off his family, so Terry said, 'Well let's go straight into it, let's have presents around and let's give you a daughter. Hey! I've got a daughter!' (My daughter at that time was only 1 year old, she wasn't eligible.) And Terry said, 'You know Holly, I'll get Holly to do it.'

I think it was quite audacious of Terry to play it with Holly, it really worked extremely well. There were some extremely funny moments. I can remember when we had done my shot on another day, we were doing reverses on Holly, and Terry had the studio cleared, and Terry operated the camera, and Maggie, Terry's wife, was there, so it was this little family group! And me in the background. And that's when she says the memorable line about 'I see your willy,' whatever it is. So that felt very much better the second time around. I was intrigued by the irony with which the scene was originally like any other scene you have in a movie when two people sit across a desk and spin out the plot, and that by introducing a positive aspect — family — it made the characters darker. Yes, I think because that scene was eventually played with an element of humor, it actually concentrates the disturbing element much more, because if it's just desk-to-desk it is more like a stock scene out of any thriller, and you're not quite listening to the lines, you're just observing the tension between the two people. If you're laughing then you're becoming much more involved in the scene, and I think an audience is beginning to feel a sort of catharsis. You know, we've all been children, a lot of [the audience] have children, they've been through that before, and suddenly the chilling line will come through — 'There's nothing I can do for you, that's it,' you know? — and I think it makes those lines much more memorable, makes Jack's attitude much more memorable. And also the point is that I don't think Jack has to be seen to be nasty in that particularly scene. What we've had is two disturbing things: one is, you come in and you see there's blood on his coat, you assume he's orchestrated some awful torture. The next thing is, he's playing with his daughter and he says, 'Well, we'll just have to get rid of him' or whatever he says. And then in the next scene you go into the real implications of what's gone on in this nice little family scene. So the interesting thing was, it wasn't necessary to put it all on the line: here's a nasty man saying nasty things. Here is a nice man having a good time, but oh Crikey! What he said! This is what it means, you know, when you're away from the family background, you see exactly what the implications are and they're very unpleasant. In the torture chamber at the end, in the re-edited syndicated version, they inserted a closeup shot of the two of you, face-to-face. You can see anxiety and sweat on you face as if you worry for the both of you. Whereas in the regular version of BRAZIL, we do not see you face, so you sound worried only for yourself. What do you as an actor think about the ability of a director, an editor to reshape a performance with a bit here, a tweak there? Well, I have no illusions: Actors are hacks basically! The real power is in the hands of the director, the editor, and enormously in the hands of a distributor. I believe, it doesn't necessarily change the movie, but they can make or break the fact that your performance is seen or not seen. But the real power lies with the director, the editor, and in some cases the producer and the studio, and that's the fact of life. You do the best you can do and you hope that you offer them in every way the best you can possibly give, so when they come to put it together, you know you're not discredited, you're not seen to be doing an uninspired, soft, flabby performance. I think if you as an actor, or I as an actor, are asked to do a performance which is not good, and I feel this isn't good and I feel I'm not doing it right, I think you really ought to be able to say so. That is about as much power as an actor has. And they may say, well we've paid your money, just do it the way, do it the way we want it done. And you sort of have to fulfill your side of the contract. Actors have very little power indeed, in spite of the vast amounts of money they give you. How did Terry's fight with Universal in the Sates play in the U.K., if it did at all? Was it seen as Hollywood dealing with an outsider, or as Americans dismissing a British film? I think that the battle, Terry Gilliam versus Universal and Sid Sheinberg in particular, made very little impact over here. I think the film had been shown here first, but Terry's films have never done as well here as they've done in the States, and I don't think that BRAZIL was, at the time it was shown here, as successful commercially as it deserved to be. So the battle in Hollywood was something which happened in Hollywood, it was largely seen as an American matter between Americans rather than an Englishman, 'cause Terry you know always been in England, had been in England for a long time, he's associated with a lot of English comedy, was seen by most English people to be American. Oddly enough, a lot of Americans regarded Terry as English! But I think we we probably did not get a lot of feedback on Terry's battle with Sid Sheinberg, except that when it was mentioned over here, and I'm sure there were, you know, people who covered it, it was seen as a sort of David and Goliath thing and evidence of the heavy hand of the Hollywood producer trying to change a movie. But because BRAZIL had not made a terrific commercial impact over here, I don't think it was the same as if you were trying to change the ending of a film that was a huge success, you see what I mean? Python had their share of run-ins with powers-that-be, with censorship and so forth. Did it surprise you what Terry had to go through with this film? I didn't honestly think that BRAZIL was as likely to cause controversy as a film like THE LIFE OF BRIAN. I think we all realize when you embark on a Bible story that you're going to get certain groups of people [who] either believe every word of the Bible, or believe that the Bible is not something to be dealt with except in sort of reverential terms. You know, those sort of people are going to give us a bit of trouble, and are going to criticize if you do a Biblical comedy. But BRAZIL didn't seem to me to be offending that that same group at all. And I never had the feeling that there was a group of people that were going to be particularly offended by the contents of BRAZIL. So I was quite surprised by what was happening at Universal. But on the other hand, I was always aware that Terry likes to sort of control things himself. He was audacious. He did like to create something that was not exactly controversial but was bold and different and unusual and he wanted to do it his own way. And he believed and he does believe in everything he does. He has a vision and an imagination which if it starts to get watered down is nothing — you've got to do it in a full-blooded way. And that's how he had approached BRAZIL, and I think just because of the length of the movie and also because it didn't have a happy ending — it had a curious, perplexing, enigmatic ending — that was what people at Universal were worried about. Which is very, very different from being concerned about offending certain groups, having their cinemas, their film picketed. It's just that they were perplexed by BRAZIL and they wanted to make it into something which was what they understood. But they'd bought Terry Gilliam, and Terry Gilliam loves riddles, and he loves making mischief on film, and he loves to be audacious, he loves to be daring, he loves to be original and fresh. All these sort of things was a red rag to Sid Sheinberg, who said, 'But we have no precedents for this; therefore let us remake this film in the likeness of films we've made before, then we'll be okay. But we have no precedent for this, we don't know how it's going to perform, it's cost us a lot of money' — uh, actually it didn't cost them a lot of money but, you know, it's going to cost them a lot of money to put it out — 'We're going to have our say, we're going to make it into something that we understand.' And I think that people get the wrong end of the stick with Terry, you know? You shouldn't have to understand everything he does. You've got to feel it, it's a very sensual thing, and that's not an easy thing for Hollywood to take on board. But it was no way the same problem as we had with BRIAN or Python. Was Terry's response throughout that period not surprising to you, given how closely you'd worked together before? Uh, not really no, it was a development on from what I knew of Terry. I mean, Terry was always uh, he liked an argument, he liked a bit of a dialogue about his work, he liked to work things through and convince people he could do something which no one else could do. And I suppose from his very beginnings of his work with Python he did achieve something which was quite extraordinary, no one else was doing those sort of cartoons and certainly not on the tiny budget that Terry had, virtually doing it all himself. None of us told Terry how to do his animations, which was interesting whereas the rest of the scripts of Python would be all up for discussion. You could say, 'Well John, I don't like this thing you've done here,' or John would say, 'Eric, I don't like that,' Eric would say, 'Mike and Terry, I don't like what you've written there.' Terry did go his own way with his animations, and I think having worked with him on JABBERWOCKY, he had a very special vision as to how JABBERWOCKY was going to work. And he was always sort of, 'All right, I will show you, I will show you something wonderful and then you can tell me whether you like it or not,' rather than, 'What do you want me to make? How should I do this? Please give me your advice. Tell me.' Terry said, 'No, I think I know what I'm going, I want to do. And this is it.' And the same with TIME BANDITS. But Terry's battle with Universal over BRAZIL was raising the stakes. Terry had battles with the BBC, or possibly with a film producer in Britain but he never really sustained it on a level he did with BRAZIL. But he felt, well, Hollywood holds all the cards, you know, they're the sort of people who sort of tread firmly with a great heavy foot on things they don't like, so I'm going to fight back in their way. So he did things like take full-page ads in VARIETY which is something that normally a studio would do and Terry took it himself to Sid Sheinberg: 'What are you going to do with my film? 'That was great! That was elevating care and love of your film into a real fighting form, and I learned a bit more about Terry from that, about his determination to take on anyone. One has to remember that Terry originally came to England because he was bored by the institutions of American entertainment — not with the talent or the creative people, he worked with brilliant people on Mad Magazine and other things in the States, but it was just the way they were marketed and the way they were dealt with by the producers that depressed Terry. So he came to England where there was more chance of not only writing fresh and original stuff but actually having it shown. Fifteen years after Terry started writing with Python, here he was trying it out on Hollywood. It had worked in England, he'd been given pretty much carte blanche to write what he wanted to do, he had proved its worth and people applauded it and loved what Terry did, and so he had a bit of determination to have a go at America. They produce the same attitude, and so really the attitude he was trying to get away from when he left America came up again with Sid Sheinberg and Universal, and it was a red rag to a bull. And Terry obligingly lowered his horns and went in! From the time you worked with him on Python, HOLY GRAIL and JABBERWOCKY, to later with TIME BANDITS and BRAZIL, how did you see his directing style evolve, become more collaborative, more verbal, more confident, etc.? Well, Terry became more confident with actors as he goes on, as you would expect. His early experience with Python was to come from the ranks of being really an animator who worked in his own little loft producing inspired stuff but on his own, and doing occasional performances on Python, which he did and they are much treasured! He appeared in a suit of armor hitting someone with a chicken; that was the great Terry Gilliam in there! But it was quite something for him to then mix with the group in the same way as all the rest of us had been mixing. Because during the television series Terry worked very much on his own, he didn't come to group meetings nearly as often as the rest of us.

We were making our first movie for a small amount of money. There were tensions; for instance, you know, we were doing a scene where we all have to kneel down, rather uncomfortably, while a rabbit is dropped on us or something like that. And then he works and then Terry Gilliam says he would like another shot because the sun is now at a lovely angle, just glinting off the top of John's helmet and I remember John just saying, 'Fuck the helmet, you know, fuck the sun! It's late, it's quarter to seven, it's time to go, I'm extremely uncomfortable, that's it!' So, that's what Terry had to put up with there. I think he had to learn ways of dealing with that, and the Pythons were not an easy group to work with. JABBERWOCKY, which was the first film he did on his own and which I was in, was extremely uncomfortable, and a lot of us sort of questioned the amount of discomfort and dirt and all that, but we did it for Terry because he so clearly believed in it, and also because he had a great eye for creating a sort of handsome picture and a good frame and nice characters. And at the end of JABBERWOCKY a lot of people said he's really good, his first solo and it was a beautiful looking film. But I think he still hadn't licked how to deal with actors. I think Terry was almost too deferential to actors, too respectful, and didn't really know quite how you got the best performances out of actors. You get the light streaming in the right place, you get the look of the scene, you know, just fresh and different and unusual and not like anything you've seen before, and then he would expect the actors to come in, do their lines and go. Which is, you know, quite permissible; that's the way a lot of directors direct, and they do it very well. But I think probably as Terry moved on to dealing with the bigger stars, I'm thinking really post-BRAZIL when he was doing FISHER KING and TWELVE MONKEYS, he had to find a way of working with people who needed him a lot, needed a director to spend a lot of time with them. When he was working in England, the English actors just got on with it really. I can't remember anybody going up to Terry, you know, 'Terry, how should I do this, please tell me, am I right, do I look good, is this the way my public should see me?' There was none of that — you just got on with it, and I think Terry was happier with that. But I think probably that he has certainly learned how to deal with actors more now, he's got a great deal more confidence, I think it probably shows in the fact he rather deftly handles a lot of good actors and thus produces some great performances.

|

copyright 1996-2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

Well, this we did talk about. We talked about the nature of evil, if you like, and the way it manifests itself. And Terry and I both felt that it is a cliche and possibly a sort of absurd generalization to think that all evil people look evil and they have scars on their faces and go heh-heh-heh and all that. We felt that very often the most dangerous people are the ones who appear most plausible and most charming. So that was how we set about the idea of playing Jack Lint, as someone who was everything that Jonathan Pryce's character wasn't: he's stable, he had a family, he was settled, comfortable, hard-working, charming, sociable — and utterly and totally unscrupulous. That was the way we felt we could bring out the evil in Jack Lint.

Well, this we did talk about. We talked about the nature of evil, if you like, and the way it manifests itself. And Terry and I both felt that it is a cliche and possibly a sort of absurd generalization to think that all evil people look evil and they have scars on their faces and go heh-heh-heh and all that. We felt that very often the most dangerous people are the ones who appear most plausible and most charming. So that was how we set about the idea of playing Jack Lint, as someone who was everything that Jonathan Pryce's character wasn't: he's stable, he had a family, he was settled, comfortable, hard-working, charming, sociable — and utterly and totally unscrupulous. That was the way we felt we could bring out the evil in Jack Lint.

So I think several months after we'd shot the first scene, we got back together again and it just felt easier, it felt better. I enjoyed having Holly there, it gave me something to do which enabled the sort of jargon and the sinister side of what Jack is saying to come out as though he's just sort of playing with his girl, playing with his family at the same time he says these things about, 'Well, you have to be destroyed, you'd have to wipe him out,' and all that sort of thing.

So I think several months after we'd shot the first scene, we got back together again and it just felt easier, it felt better. I enjoyed having Holly there, it gave me something to do which enabled the sort of jargon and the sinister side of what Jack is saying to come out as though he's just sort of playing with his girl, playing with his family at the same time he says these things about, 'Well, you have to be destroyed, you'd have to wipe him out,' and all that sort of thing.

When it came to the first bit of directing which was MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL Terry had to sort of interrelate with the rest of them and he clearly has that amazing sort of visual sense of imagination and beauty, and Terry makes beautiful pictures.

When it came to the first bit of directing which was MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL Terry had to sort of interrelate with the rest of them and he clearly has that amazing sort of visual sense of imagination and beauty, and Terry makes beautiful pictures.