THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // TIME BANDITS (1981) |

Sizing Up a Legendary Film |  |

|

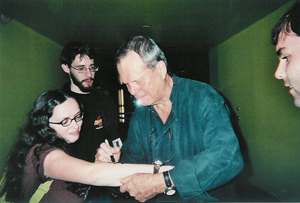

Shortly before the U.S. opening of TIDELAND, Terry Gilliam embarked on a whirlwind promotional tour in New York City, including screenings, leafletting outside the studios of THE DAILY SHOW, and some heavy autographing sessions (including one young lady who — perhaps not knowing, or caring, that sharpies are permanent — asked that he autograph her arm). Gilliam also hosted a screening of TIME BANDITS at the venerable Film Forum. The enthusiastic response of the audience — many of whom hadn't even been born yet when the film debuted in 1981 — gave it, and him, a warm reception. Today, looking back on his sophomore solo directing effort, Gilliam sees unusual associations with his later work, as well as a fond feeling for a movie that, against all odds, stood toe-to-toe against bigger, more expensive Hollywood films and — like its eponymous heroes — proved victorious.

Midnight sunshine silent thunder It's 25 years! I'd not seen that film and I'm been doing a lot of interviews today for TIDELAND which is in a strange way 25 years on from this. They both start with "T-I" and they both involve children's imagination and they're very, very different films. I'm not sure if the world has changed or it's me that's changed in all that time. What was great about this, I was trying to do BRAZIL. We had started a company called Handmade Films, it was how we made LIFE OF BRIAN, because EMI Studios at the last moment — we were all ready, the crew, everything was about to head down to Tunisia to start work on a Saturday, and on Thursday EMI pulled the plug and said, 'no.' And Eric Idle went to George Harrison and said, 'We're in trouble,' and George said, 'Well, I'll give you the money.' And BRIAN was made and we — Python and George — joined to make Handmade Films, which made this film. And I was trying to get another film off the ground through Handmade, a film called BRAZIL, and Denis O'Brien who was running the company didn't understand and he wasn't interested and he kept stalling, and so in frustration one weekend I said, 'I'm going to write something for all the family,' and that's what you just saw. And I basically wrote the story and then I called Mike Palin up and said, 'Mike, would you work with me on this?' And so, the words are his, and the characters and everything grew. But the idea was in a strange way what relates to TIDELAND — I'm selling TIDELAND, you may have noticed — is that I was worried the child would not be able to sustain the whole film, and so I said, 'Well, there's only one way around this problem which is to surround him with a gang the same height.' I think my original idea was that these people were not satisfied with Heaven, and life on the run, robbing and pillaging through history, was much more interesting. And then the idea that you commit a crime and then jump to a time before the crime was committed, it grew like that.

What else could I tell you about it? I'm not sure, it's more about what you want to know than what I can tell you, so I guess let's do questions.

Not really. Probably in the back of my mind, way back there there's some very cynical side that's saying, 'Yeah, we could actually do that!' I mean originally there's a character in with Evil, who is the seventh dwarf, cause there's basically six little guys, the seventh there's a whole story about Horseflesh that Mike and I worked on but in the end we didn't use any of it. He's there but he wasn't developed. When we started the thing I was under a lot of pressure — by again Denis O'Brien, our manager at Python and George's manager — to use a lot of George's songs. He can see it's a lot like the seven dwarves — a lot of 'Hi ho, hi ho, it's off to work we go.' I said, 'No, that's not the kind of movie we were making.' But in fact George did write and sing that end song, which I tacked on, and I didn't realize until much later it's his notes to me about the film. And there's a line in there about "Amaze without taking up time" — It's just fucking long, Terry! — and it's all in the wonderful notes there. I was just listening to it and it was reminding me of what a clever sneaky little bastard George was. I hope you all heard that. 'Equally great as TIME BANDITS, TIDELAND!' Actually it's funny because I wasn't even thinking about this when I was making TIDELAND, but it's only having to do this that brought this connection together, and I think you're absolutely right, they're very similar in a sense of what a child's imagination can do. And interestingly enough, this film ends with the parents disappearing, blowing up; in TIDELAND it doesn't take long to get rid of them.

Now on the questionnaire — and this is stuff that every filmmaker has to go through, dealing with these statistics that come at the end — when the audience votes, one of the questions is, 'What is your favorite part of the film?' And one of the answers was, 'The End.' And what happened was, I took the cards home — again, people don't normally do this, but I took them because it's very nice to read them, you can see the handwriting, you can see the anger, you can see the joy, all those things, there's a person who's writing this stuff — and it was clear because of this terrible sound system and so many people leaving, the part they liked best about the film was the end — it was over, is what they meant. But when you saw the statistics the next day, the part that was most loved about the film was the end — which was the parents blowing up! And so I won and got the parents blowing up. Again, what was interesting about how children watched this film, I remember adults when they came out they were very uncertain — they were worried because it moved so quickly, jumping around in time and space. Children, they just went for the ride 'cause it was entertaining, and it was the parents that were always worried about that. But anyway the film came out and it worked, so that was really the beginning of my career. Actually what it was, when BARON MUNCHAUSEN came out, I said it was the fourth part of my trilogy, just to confuse people. But it was only in the making of BARON MUNCHAUSEN I kind of realized what was going on here, that we've got the child, the man and the old man, so I took full credit for having done a trilogy. I never think about these things, it's only later I discover what I've done because somebody points out the obvious, which I missed.

I mean, I don't know. At the moment everybody is very confused about where the business is going, with DVDs, with the web, it's very confusing, But I think there will always be that big pot of money in the hands of a few people who are very nervous. At the moment the studios now are really not even run by entrepreneurs or people who understand or are interested in films — it's middle management, 'cause all the studios are owned by a larger corporation, and they're living in a world where quarterly statements dictate everything. So you have a lot of people who are being paid a lot of money who are terrified of making movies. Their basic function is to say 'no' because they're safe when they say no. If they say 'yes' and the film flops, [slashes neck]! They go. So that's just the system. I don't know, unless something extraordinary happens I think it's going to be with us for a long time. When I go to Hollywood, I'm usually coming up with a project that to me is fresh and new and exciting and that's what terrifies them; they feel the need to remake things that worked before, they want comfort. I'm just so perverse, I like making their lives a misery, but I've probably suffered more than they do for it!

I would like to be when I grow up! Actually I'm not trying to make elitist films or difficult films. I'm actually trying to reach a large number of people and I keep failing! On the other hand, TIME BANDITS was a big success, FISHER KING was a big success, TWELVE MONKEYS was a big success. So I've done enough that allows me to do what I do, but I'm not really thinking about the audience as such because I don't know what an audience is. I know what individual people look like but I don't know an audience. So I make things that excite me that I believe in, and I assume I'm somewhat part of the human race, there must be a couple of other people like myself that have similar taste, and I'm relying on that. It's as simple as that. And I've always been in that situation where I feel, after a certain number of less financially successful films, I've got to then do something that will make some money. But it's such a gamble, and I can't predict anything. So I'm getting old, and I going to die soon, so I just make what I like. I really just try to find the best actors I can get because they make it look like I know how to direct actors. There's no theory to it. Either there's an image in my head or I bump into somebody who surprises me. The only time we ever cast based on the script was this film, because Mike and I wrote in the scene with the Greek warrior, after the battle with the Minotaur, he takes his helmet off revealing himself to be none other than "Sean Connery, or an actor of equal or cheaper stature." That was actually in the script, 'cause we had no idea that we would ever get Sean Connery. It was our little joke. And Denis O'Brien, who was our manager, was playing golf with Connery, and Connery's career at that point was really at its nadir — he'd done some wonderful films that weren't working — and for whatever reason he liked the idea of this and he came on board. And I think it was very important to the success of the film. He's such a surprise, he's amazing. But normally, the characters seem to be in my head and I hunt people down. But what I've loved is finding people that I'm not expecting to like who are actually even more interesting for the part. Always when you're working on a project over a long period of time you kind of get into a rut about thinking, and I try to shake myself out of it by some interesting casting, but the main thing is to get really good actors — and also people who are going to be enjoyable to work with, because you're going to be stuck with them for a long time, so hopefully we all get on. It's become a bit of a legend, it's not really true anymore. Journalists tend to be lazy and they just keep repeating themselves, so it's not actually true. My big fight was over BRAZIL which was very public and after that I didn't really have that many fights until the Weinsteins came into my life. But that's something else. And in fact the studio films that I've done, the ones that actually were in Hollywood — FISHER KING, TWELVE MONKEYS and FEAR AND LOATHING — no problems at all. So it's a bit inflated, that one. I think it's partly because I have people making documentaries about the films that I make or somebody writes a book. So whenever there is a fight — and there's always fights on every movie, everybody, every director has fights — then these get written down or in a documentary so they're recorded and then they're available for public consumption. Most battles are done behind closed doors and never allowed out. I just am so lazy I don't like diaries so I have people write books or make documentaries, they're really for me, just to remind me what it was like and hopefully encourage me never to do it again. That's what's good about them. But I do have this reputation and I'm getting tired of it to be quite honest! It's not accurate.

I've been working on it this year, in fact I just rewrote the script a week ago. It's an expensive film, that's the problem, and it means I've got to get some A-list actors to get the kind of money I need, and most A-list actors aren't right for the part. And so I'm in a bit of a quandary. But I'm actually working on it at the moment. Whether it happens or not . . . This is a project that's based on a wonderful book by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett and it's about the Apocalypse, it's a comedy, angels and demons and the Anti-Christ. It's a wondrous book and I think we made a pretty good script out of it. Before BROTHERS GRIMM, we had a budget of $60 million — we actually couldn't have done it for that, we lied! — but we raised $45 million outside of America, I needed $15 million from Hollywood and I had two actors to play the Devil and the Angel, it was Johnny Depp and Robin Williams. And I couldn't get 15 million dollars out of Hollywood! That was the time when Johnny was doing CHOCOLAT and THE MAN WHO CRIED and they said, 'Well, he just does those European art movies, he's not worth it,' and they thought Robin's career was over. That was the end of that one. And then along came PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN(!). That's what's awful about Hollywood: they don't really understand the talent they're dealing with, who they're dealing with, how and why people work. And now of course Johnny, put him in anything and you can get any amount of money you need. But that's a product of him sticking to his guns and doing the kind of things he likes doing because that character (Captain Jack Sparrow) when they were shooting that film, I talked to him, and he was being beaten up by the studio over his terrible mascara all over his face and his faggy performance — I mean they just hated everything he was doing — and he is the reason it was successful, almost singlehandedly. Anyway, I don't know what happens with it. We work, we go on. TIME BANDITS? Oh God. The most difficult part of TIME BANDITS was the beginning, because I hadn't shot a film for a couple of years, since JABBERWOCKY. And we started in Morocco on top of this mountain in 130 degree heat with Sean Connery and a boy who had never been in a movie before. And I had my storyboards — ambitious, like 30 shots in one day, not possible! And it was heading toward disaster on Day One. And it was Sean who said, 'Listen, shoot me, get me out of the thing and then you can play with the boy.' Things like that. 'I'm not going to let you shoot me getting on the horse, I'm going to look like shit, so I'll just stand in the stirrups and I'll lower myself down. Goodbye, kid!' And it was so shocking but he got me through it because I threw everything out, I got these few shots, got him done and went straight on to the boy. The rest of it was really quite fun. Where it went a bit crazy was at the end, the big battle with the tank and the cowboys and the archers and all the rest. We had a big problem with the special effects, none of the stuff was turning up on the right day. And so I had to shoot that completely out of sequence, there was no connecting tissue on any of it. I just had my storyboards and I'd get that shot in and then the tank wouldn't work. 'OK, forget about the tank, let's go and do this!' And we'd shoot that. And the focus puller was a guy who'd been on so many films, he'd done LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, he was a real pro, and they all thought I was out of my mind, this will not work. And then he saw the film cut together and he said, "I can't believe it but you did it." At that stage I just had to rely totally on the storyboards because I didn't have the confidence to just wing it, but in that instance it was fantastic to do sort of shot-shot-shot and then you stick the jigsaw together at the end and it works. Originally in that big battle when all those archers appear, it was Sean Connery's re-entrance into the film and he was supposed to be leading a group of archers, and he was the one who was supposed to be crushed by the falling column. But we'd run out of time with Sean, we only had X number of days with him, and we couldn't do it. And so overnight I rewrote it so we killed Fidget instead — I said he was the cute one, let's kill him — and the archers were just there. And then we got to the end of the film, we didn't really have the good ending and I remembered my first conversation with Sean and he said, wouldn't it be great if at the end he played the fireman? And I remembered that he just happened to be in London because he was a tax exile then, he had one day [when] he was on his way to see his accountant and I said, 'Stop by the studio.' And he stopped by the studio, I put him in a fireman's outfit, did two shots — one where he puts the boy down, winks, and then he climbs in the cab, shuts the door, winks. That was it. I didn't write the scene until a month later, it was shot with doubles, that whole end sequence, and it works! I think I learned on that film, if you're in a situation where you're really in control, you've got good people around, work fast, we come up with different ideas. There's another scene that's interesting — we actually shot but it isn't in the film. It's the spider women scene. Because after they escape from the boat on the giant's head, they're in — some place, it doesn't matter, and suddenly Og gets grabbed by this tentacled thing, dragged into this cave and they chase him in there, and there's these two women with 6 or 8 legs and they all sit there in this Edwardian [room] and they're knitting away, and what snagged him was their yarn, and around him in this big spider web are all these young blond knights in shining armor they captured for boyfriends. We shot this scene and then we ran out of money, because it would have meant that we had to shoot the scene on either side of it, which we couldn't afford. Pushed into a corner, it was one of those days I said, 'I got it, they're already there, there's an invisible barrier and they can't see the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness,' so we went and shot that scene which costs next to nothing because an invisible barrier is very cheap. You go [mimes putting hands against an invisible wall] It works! And that was, to have that kind of freedom, and have Mike there, between Mike and I we could invent anything whenever we needed to. It was a great time. Actually, another thing I don't know if you noticed at the end when he's approaching the pile of ashes [of his parents], you notice the smoke is going backwards? OK, here's why: Because we weren't able to afford a proper crane and all we had was this cherry picker and it was supposed to be pulling up, but it was going up in jerks. I said, 'Well, this is no good,' so we started the shot up there [going down], and it's all shot in reverse, Craig Warnock, the little boy, is walking backwards in the shot. The other one where they worked backwards is when Ralph Richardson and the gang are sucked up to Heaven, all that smoke was all backwards, everybody's acting backwards. Simple!

My biggest fear was that they would overdo themselves. There was one day, because Tiny Ross who played Vermin, he's a very old guy and he used to live out in Wales and when he wanted to talk to anybody he had to bring a box to the phone box that was out at the end of the village, put his box down so he could climb up and call. And he was on that horse during the end when the cowboys arrive, he was sitting on the back. I left the studio for about 15 minutes and that day there was a new first assistant director on, a temporary one. I said, 'Be really careful, these guys will push themselves beyond their limit.' And I got back a few minutes later and there was Tiny with a broken arm. That scene was shot with his arm in a cast, and it's hidden behind the cowboys. So the guys were extraordinary. I just, I really loved them. The funny thing was, when we were cutting the film, we had to do one little scene much, much later. [And] I would shoot them so you can't tell how tall or short they are, [so as] we were cutting, you get so used to seeing them in the scene as normal-sized people, and then we had to do this reshoot and over the hill came these teeny tiny little people. Jesus! These are the guys I've been working with all this time! Unfortunately not many of them are left. I think Mike Edmonds (Og) is still around. David Rappaport (Randall) went out to Hollywood, became very successful, he was doing a television series, and like Hollywood does to people no matter how successful you are, there's somebody more successful, and he blew his brains out. I've had two friends who've committed suicide in Hollywood, so that's one reason I don't like Hollywood. I'm actually thinking of suing George Bush and Dick Cheney for making a remake of BRAZIL without my approval. Their version isn't as funny, though. Reality has caught up and passed me! It is absolutely frightening. Homeland Security is just like the Ministry of Information, because if your job is counter-terrorism, what do you need to keep in business? You need terrorists, and even if they aren't there, we may have to create new ones. It works very well. So I congratulate the two of them on their remake of the movie.

Lyrics from "Dream Away" by George Harrison for the film TIME BANDITS (1981)

|

copyright 2006, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

And again what was interesting, dealing with studios as I have over the years, we went to the studios with the script and nobody wanted to know about it, So George once again put up the money to make the film. We finished the film, the finished film you just saw was taken to the studios, they didn't want to buy it. And so we ended up with a company called Avco Embassy, which was the smallest of the mini-majors, and they hadn't had a hit for 10 years, but they had a distribution system. So George and Denis O'Brien guaranteed the prints and the advertising and we used basically their machinery for distribution, and the film opened, and I didn't think it was going to do much and it ended up number one for five or six weeks. It is still the most successful, financially successful film I've had in America, but what it did do was give me enough credibility that we could make BRAZIL. So it was a very important film in my life.

And again what was interesting, dealing with studios as I have over the years, we went to the studios with the script and nobody wanted to know about it, So George once again put up the money to make the film. We finished the film, the finished film you just saw was taken to the studios, they didn't want to buy it. And so we ended up with a company called Avco Embassy, which was the smallest of the mini-majors, and they hadn't had a hit for 10 years, but they had a distribution system. So George and Denis O'Brien guaranteed the prints and the advertising and we used basically their machinery for distribution, and the film opened, and I didn't think it was going to do much and it ended up number one for five or six weeks. It is still the most successful, financially successful film I've had in America, but what it did do was give me enough credibility that we could make BRAZIL. So it was a very important film in my life.

On TIME BANDITS, this is the only big battle I was having — over the ending. The idea of a children's film where the parents blow up was not possible. And we had a screening in Fresno, California, one of the NRG screenings where they hand out the cards that you fill in. It gives the audience the chance to have power over the filmmaker, and they really grasp that power! But something was wrong with the print — it was either the Dolby print or it wasn't a Dolby print but it went through the wrong sound system — and so the first third of the film sounded like mmphfhphm mfhbmle thfmphfl mpthmfswmem — people were leaving.

On TIME BANDITS, this is the only big battle I was having — over the ending. The idea of a children's film where the parents blow up was not possible. And we had a screening in Fresno, California, one of the NRG screenings where they hand out the cards that you fill in. It gives the audience the chance to have power over the filmmaker, and they really grasp that power! But something was wrong with the print — it was either the Dolby print or it wasn't a Dolby print but it went through the wrong sound system — and so the first third of the film sounded like mmphfhphm mfhbmle thfmphfl mpthmfswmem — people were leaving.

I was a patron saint. I was canonized I think. It's been very strange. It's very interesting because I've been a lot of places and all the little people all used to come up to me and say, 'Thank you for treating us like human beings.' That's part of the thing I wanted to do. I was so tired of seeing these guys in Womble costumes, stupid costumes, or tin cans like R2D2. And I thought, here is a chance to let people be heroes. Alan Ladd was short, and he was a hero, so why shouldn't they? And they were fantastic 'cause all these guys just rose to the occasion.

I was a patron saint. I was canonized I think. It's been very strange. It's very interesting because I've been a lot of places and all the little people all used to come up to me and say, 'Thank you for treating us like human beings.' That's part of the thing I wanted to do. I was so tired of seeing these guys in Womble costumes, stupid costumes, or tin cans like R2D2. And I thought, here is a chance to let people be heroes. Alan Ladd was short, and he was a hero, so why shouldn't they? And they were fantastic 'cause all these guys just rose to the occasion.