EDITORS // "MO' BETTER BLUES" (1990) |

Rhythm And Blues

|  |

|

Sam Pollard's background was primarily in documentaries, serving as a director and producer of PBS' EYES ON THE PRIZE, as well as the specials PAVAROTTI IN CHINA and episodes of NOVA, when he was enlisted for Spike Lee's music drama MO' BETTER BLUES. In March of 1990, he spoke of his collaboration with Lee and his take on the film, which merged his documentary experience with his love for jazz music.

Morgan: What interested you in doing this film? Pollard: It's about jazz music. To me, jazz musiciansare like gods. I love jazz musicians, I have since I was 10. Most times when I see a film about jazz musicians, BIRD, `ROUND MIDNIGHT, even that disappointed me and I love Dexter Gordon. When I heard that Spike Lee was doing a film about jazz musicians, [with] his background — his father is a jazz musician, he's been around jazz musicians all his life — [I thought] this has got to be interesting. With your background in documentary filmmaking, what do you think you bring to your job as an editor for a fiction film? The whole last sequence of the film, the montage to the music of LOVE SUPREME is all documentary, the stylistic approach. When I cut a dialogue scene, I've got to make it the puzzle it is, because to me when you cut a dialogue sequence it's like a puzzle; she's got to say this and say that, but in the documentary thing it's like, I've got to make it up. He's shooting this footage and giving it a rubber band quality so it will be spontaneous, and it's my job to make it still seem spontaneous. My biggest contribution to this film is my enthusiasm, my love for the music. Jazz musicians are warriors to me, they always have been. Being an editor, what you have to contribute is that you always have to be able to say, when the director says, 'Let's try something else,' you've gotta be able to want to do that, which means that you can never be fully satisfied with what you've got. You've got to be ready to change. I know the music. Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, I would suggest Ramsey Lewis' "The 'In' Crowd," or Mingus' "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,' that's a good version, we should try that. The pace and the feel of this film is like Miles Davis, playing "So What," "Beautiful Girl from Calico" or "Someday My Prince Will Come." It's got that kind of feeling; when the rhythm is there, that's the feel of this film. It's got that tempo. And there are times when it bursts out, and the rhythm is this — Miles may come up with some funny notes, saxophone — and as the film progresses to the end, it takes on a spiritual quality. It starts with that Miles Davis, very cool, slick style because the film focuses on Bleek Gillian and his world and the selfishness that he has, and now he's got to change himself as a person to be a better person, and he realizes that. The movie turns and takes on the spiritual quality that John Coltrane found when he left Miles Davis and formed his own group, and reached the heights of "Love Supreme" in the `60s. The film it starts to get languid, more spiritual. That's my take on the film. That's what it does: it starts off like Miles, that real cool, slick style he had in the 50s, early `60s. Then it transitions into Coltrane's spiritual quality. It's like the ritual of life, it's watching rituals, it's watching life. It's like looking down and you're seeing life, a world, a community. It has different aspects of it, different people in it. Every once in a while one person will stand out more than the others, but you're getting a sense of a community and a world. I would say that Spike is that kind of filmmaker. I had a talk the other day with a playwright and he used this term. He said Spike's films are like rituals. It's not really story-driven — there's a story there, but the story comes out of understanding the characters. It's tough sometimes to touch, to grasp and hold onto, because Americans are so story-oriented. It's an experience. We watched the rough cut about 3 weeks ago, it was like watching a European film by Bertolucci or Resnais. You're watching and you're seeing their moments. The Bleek Gillian character, that I can touch. I know that character. I know, I feel kinship with that character, because his sense of loyalty, his selfishness about his music and himself, [is] something that I identify with, so I'm right there with him. I empathize with him. There needs to be a tension between people for a piece of work to go beyond being just okay. Sometimes you need that tension to force both people, whoever's involved in it, to spiral the work upwards. Sometimes you've got to manufacture the tension, but you've also got to be able to know when to pull back, and to give the other person, who's the director (in this case Spike) to let him run with it and be open to what he's saying. How are you cutting this? Steenbeck. I grew up on Steenbecks, Spike has too. I cut video, but with the Steenbeck you can touch it, you can feel it. It's real different when you press the buttons, which I've done. You need to really touch it to get into it. When Spike said he wanted to cut in 10 weeks, I said, 'Nobody cuts a documentary that fast.' You cut a documentary you're only talking about 80,000 feet of film, and you've got 10 weeks for a rough cut, and 6 more weeks to hone it and tune it. You won't cut 300,000 feet of footage in 10, 12 weeks, you just don't do it... And we did it! You push, you push, you push yourself, and you don't have to worry about pushing Spike because he's pushing himself, too. Though you haven't worked with Spike before, you know his films; how do you think this film will differ from his earlier work?

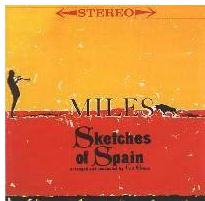

How did your collaboration develop? And did you contribute advice towards other areas of the film, such as during the shooting stage? I'm coming from the outside. I guess if I worked with him on a second film I would probably get more involved in expressing how I react to different scenes. I guess there was on my part a certain hesitation to become too vocal. When I read the script, I said I thought it was a good script, and I remember I called him a couple of weeks after to suggest a way to envision the opening. I told him if he remembered the Miles Davis SKETCHES OF SPAIN record cover (right), Miles in silhouette, it would be a nice way to think about that, different angles of Bleek playing and holding his trumpet. I never really said much about how he should shoot something. I didn't know him that well, and I didn't feel that it was my place. I feel I've gotten to know him the past five weeks. Postscript: Pollard has since worked with Lee as the editor of GIRL 6, CROOKLYN and CLOCKERS, BAMBOOZLED and WHEN THE LEVEES BROKE. He produced the HBO documentary 4 LITTLE GIRLS, and directed the "American Masters" documentary MARVIN GAYE: WHAT'S GOING ON.

| |||||||||||

copyright 1990, 1997, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

It comes from a bigger budget, and having more opportunities to do more types of things. more of a shooting schedule, and more mobility. So with this one he's opened up, he had opened it up with DO THE RIGHT THING, it was a fabulous film. You can see that he's growing, using everything that a filmmaker is given in terms of technical tools to create.

It comes from a bigger budget, and having more opportunities to do more types of things. more of a shooting schedule, and more mobility. So with this one he's opened up, he had opened it up with DO THE RIGHT THING, it was a fabulous film. You can see that he's growing, using everything that a filmmaker is given in terms of technical tools to create.