ESSAYS // Nowhere To Hide (1991) |

Nowhere to Hide |  |

|

The cat-and-mouse game in Martin Scorsese's CAPE FEAR, in which a prominent attorney is haunted by an ex-con he once represented in court, gets off to an unsettling start. Sam Bowden, feeling threatened by the unnerving presence of Max Cady, tries to distance himself from a former client who had to spend fourteen years in prison. "I realize you've suffered," Bowden says, attempting to sound sympathetic. "But why me? I defended you. Why not badger the D.A.? Or the judge?" Cady is amused by Bowden's eagerness to shift blame and attention elsewhere. Coolly, he looks the lawyer up and down, and replies, "They were doing their jobs." The question of responsibility is key to appreciating CAPE FEAR beyond its melodramatic framework. For by the end of the film, Cady will have placed Bowden on trial, judging him against the proud lawyer's own standards, and finding him guilty of vanity, self-righteousness, and treason to the ethics of the Law – and, by extension, of being untrue to himself. Two parties in opposition – the generic conflict of a trial – has forever been a popular basis for stage and film drama. Vindicating the innocence of a hero, or meting out punishment to wrongdoers, is greatly satisfying for an audience, accounting for the durability of the courtroom drama genre. Because films tend to be dictated by a narrative's demands for logic and resolution, rather than by the inner life of the characters, there is little room for ambiguity; plots drive films, and characters either go along for the ride or are considered expendable. In courtroom dramas, this need for closure is satisfied by exploiting the very semiotics of a trial: a conflict raised between a protagonist and antagonist, argued by respective counsel, with the resolution coming from a judge's or jury's decision. Resolving the film drama's conflict in a rational, institutional manner thereby removes the possibility of chance events or, worse, irresolution. This is one reason why lawyers are often depicted in film drama as very black-and-white figures – characters whose function is to win or lose, to help bring about the resolution for the main characters in jeopardy. They are chessmasters in a heated tournament, each executing moves and strategies to force the other player into mate. Consequently, there is no room in most films for these lawyer-characters to explore the grayer areas of their own personalities; audiences are therefore presented with stereotypes, and rarely see into the private lives of lawyers or the internal conflicts they have about their work and their responsibilities to The Law. Martin Scorsese's CAPE FEAR is decidedly unique among recent films which feature lawyers as their protagonists. In addition to examining how the processes of jurisprudence work (or don't work), CAPE FEAR profiles an attorney whose beliefs in the law, and in himself, are shattered, in part due to his willingness to hide within the comfort and status which his profession represents to him. In addition, the weaknesses which the character of Sam Bowden harbors are brought to the surface and magnified because of his own reluctance to step outside of the role-playing and image-making processes that he equates with the functions of practicing law. This behavior, we learn, is antithetical to recognizing his inner self, or developing personal relationships. As a result, Bowden does not acknowledge his actual limitations; once he has to call upon his inner strength to protect himself in a life-threatening situation, he discovers to his horror that that is one resource which he does not possess. Instead, he finds himself increasingly plagued by self-doubt, fear, and a propensity – even an attraction – towards violence. There have been other recent films which have attempted to show the struggles of conscience in which an attorney may be engaged, over a particular case or about his life in general; but these rarely succeeded above being sensational melodramas cashing in on the time-worn elements of the courtroom drama. For example, REGARDING HENRY's central figure, a vindictive scoundrel who learns to love himself and others following a near-death experience, is defined as a lawyer only because of the filmmakers' cynical stab at making the character's ambition and egotism instantly recognizable to a jaded audience. PRESUMED INNOCENT took its source novel's intriguing idea of having the primary murder suspect narrate the story of his own trial, and forced it into a more conventional narrative format better suited to film. Consequently, unlike the readers of the book, the audience could not see into the mind of the protagonist; instead they were left with a cold cipher who just might be hiding a deadly secret. A few notable examples of films which depict lawyers as real characters with real struggles have in fact benefitted greatly from the charisma of their stars: James Stewart in ANATOMY OF A MURDER, Al Pacino in ...AND JUSTICE FOR ALL, and Paul Newman in THE VERDICT. Though varying in quality and seriousness, these pictures capture the very essence of their central characters' internal conflicts towards the law – their cynicism, competitiveness, personal tragedies, alcoholism, and their latent or burning outrage towards social and bureaucratic injustice. CAPE FEAR, however, is a rare film which – operating within the genre framework of the thriller – dramatizes the realization of a lawyer's potential for humanity after that humanity had been lost.

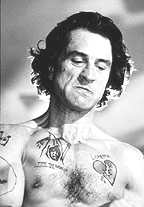

In the film, Sam Bowden [played by Nick Nolte] is a successful corporate lawyer, residing in a small town in the Carolinas. On the surface, his tranquil existence and the steadiness of his relationships with his wife, Leigh [Jessica Lange] and daughter, Danny [Juliette Lewis], bespeak a happy, fulfilled life. But this placid, 'typical' suburban family is revealed to be extremely fragile by the appearance in town of Max Cady [Robert De Niro], recently released from prison after serving 14 years on an aggravated sexual battery conviction. Once a client of Bowden's (who was acting as Cady's PD), Cady returns to seek a curious revenge upon the attorney he faults for his incarceration. The original CAPE FEAR, released in 1962 and starring Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum, was a rather straightforward revenge melodrama about an ex-con wreaking terror. This remake, however, goes further than vengeance in the conflict between Cady and Bowden. In the screenplay by Wesley Strick, it is revealed that, while serving as Cady's PD, Bowden squelched a vital piece of defense evidence – a personal report on the alleged rape victim's sexual history – which might have led to Cady's acquittal. Due to his prejudice against Cady's illiteracy, class and record, Bowden purposefully neglected to give his client the defense he was ethically bound to offer. The new CAPE FEAR is therefore not about a psychopathic convict trying to even a score; it is about a man coming to terms with an unethical, self-righteous act in his past, and how his refusal to deal with the ramifications of that event has colored all areas of his life. As Bowden fears for himself and his family once Cady begins making veiled threats against him, he finds that his privileged position in town does not protect him – he is as vulnerable as someone outside the loop of the judicial system. Because Cady's initial, ambiguous intentions hardly constitute a breach of statute, the local police lieutenant is reduced to sympathetically making veiled suggestions that Bowden take the law into his own hands. This lack of support paralyzes Bowden, and leaves him incapable of functioning at the level to which he has become accustomed. Strick, who was bothered by the original CAPE FEAR's condonation of vigilantism, wanted to create an absurdist black comedy instead of just another tale of frontier justice. "I certainly didn't want to promote the idea that guns ultimately solve problems," he said. "If you could tell the story with another kind of sensibility, it would just be more ironic and full of dread, more a fable of a thin veneer of civilization. And what really intrigued me about it was the horror of discovering that this vast and intricate support system that we all kind of assume is there for you, is not there at all; they're focused on their own sort of interests to protect. It's almost like a Kafka or Thomas Berger novel, where things seem only to get worse and worse and worse – the hero is like a drowning man, and the harder he flails about, the more he seems to cramp up and sink." One aspect of a lawyer's self-image, which is invoked by Nolte in his performance, is the persona which a lawyer may take on while he is in court. This 'mask' [which had been described by James R. Elkins in a 1978 Virginia Law Review article, "The Legal Persona: An Essay on the Professional Mask"], is a means by which a lawyer may present an image to his client, his courtroom opponents, and to the community, as being not only a representative of the law, but an embodiment of it. The characteristics of the lawyer mask are obliquely synonymous with the attributes we would confer upon the law itself; one who wears his 'legal persona' appears to be fair and equitable, removed from the painful, desperate situations of the defendant or plaintiff. This requires the subject to 'talk like a lawyer' and to 'think like a lawyer,' to in effect fulfill the expectations or prejudices of what outsiders have come to demand of lawyers (or to operate within the lawyers' fraternal bond). Such a persona has its benefits, in that it may command authority; the wearer gains credibility, and power. But perpetuating this mask has its disadvantages in that it is both deluding (by inflating the importance of the lawyer as a person) and isolating (by creating an inviolatable border surrounding a 'lawyer's world' disallowing laymen from entering). In Bowden's case, he has come to believe his own PR, as it were, by rationalizing his mistakes, thereby imagining himself to be incapable of error. Elkins wrote about the intersection between the professional and personal lives of a lawyer, and how the determination (or inclination) to appear detached, objective and in control on the job may be translated into the lawyer's private life, where such attributes are no longer an asset. If this professional mask were to dominate the individual in his relationships with family and friends, Elkins suggests, "...the legal persona is internalized and becomes indistinguishable at a psychological level from other disguises of the self. The effects of overidentification with the lawyer's role lead to rigidity and an inability to exchange masks as required by society ... Because the lawyer's role is invested with so much status and prestige and because the mask fits so well, the danger of overidentification with the legal persona may not be apparent to the individual." *

Gradually his 'role' proves more hazardous to perpetuate, and more and more transparent. The appearance of Cady shines a light upon the darker sides of Bowden's character, and forces Bowden to admit to the procedural chicanery with which he shuffled off Cady's case years earlier [what he selfishly classifies as 'ancient history.'] The Stoical figure which Bowden cuts is undercut by his less-than-stringent adherence to principles. Even his admission of the past transgression to Leigh only evokes his wife's memories of 'Old Slippery Sam,' an appellation with which she wearily characterizes his years at the PD's office. In researching his role, Nolte met both with lawyers in the Atlanta Public Defenders' Office, and with small town lawyers in West Virginia. He found a curious lack of willingness among those he met to discuss ethics – either among the big city defenders who must plead the cases of poor defendants, or the small town attorneys who are politically connected with the local businesses or governments. "You go into a big public defenders' office to see how the big system works," says Nolte, "and bring up Canon number 7 or the Sixth Amendment, and what the possible scenario is if somebody gets himself caught in that kind of situation, and they're deathly scared to discuss the ethics of it: 'Oh, you don't ever ...,' 'Oh, no, for Christ's sake, it never even crossed my mind!' They don't want to discuss it because they want it to look squeaky clean, understandably." The reluctance to address such ethical considerations corroborates Elkins' theories about the Lawyer Mask, presenting an impenetrable facade that is accepted as the truth. For Bowden, the mask works both ways, disguising the wearer from the outside world and from himself. At home, Bowden's lawyer mask had presented an authoritative figure whose function was to keep the atmosphere of the home undisturbed, respectable. Conversations between husband and wife, parent and daughter, meant to preserve the facade of a happy family, left much unspoken and therefore misunderstood. As his lawyer mask is chipped away, Bowden is surprised by the anger which erupts between himself and Leigh, as well as his expressed mistrust of Danny, as Cady attempts a seduction of her by playing off the stresses he detects in their home. Leigh, dissatisfied with Sam's inability to face up to his actions, becomes more and more fascinated by Cady and his motives, possibly making Sam more vulnerable in the process. Bowden self-righteously judges Cady as well, measuring the ex-con and his capacity for violence against the unrealistically high standards which are part of his own mask. For Bowden to then discover that he himself has weaknesses – that he is imperfect, with a capacity for brutality – is a deeply upsetting experience, greatly unnerving and revulsing Bowden. His fear thus increases the speed with which he reverts to a primitive being. Far from the uneducated hick which Bowden remembers, however, Cady is an enlightened individual, whose life has been spent learning the true meaning of Man's pain, suffering and redemption. Having taught himself to read during his prison term, Cady has steeped himself in theology, philosophy and law books. Rather than ask for his pound of flesh, Cady is far more interested in touching Bowden's soul, teaching him a lesson about human nature, which the uptight lawyer cannot at first comprehend or absorb. This is not to lead the reader to believe that Max Cady does not commit atrocities. But Cady recognizes that he has power in the threat to commit acts of violence, and he manipulates the fear in others to his own benefit. For example, he directs violence towards those surrounding Bowden, to make his ultimate prey feel trapped, as when he brutally attacks a court clerk with whom Bowden has been emotionally involved. Bowden's feelings of powerlessness in his confrontations with Cady follow another of Elkins' theories regarding the Lawyer Mask, that of the tendency for a lawyer to project a particular structure or model of court procedure onto society and the world at large. For attorneys accustomed to the patterns of discourse in a judicial setting, they may seek to impose these same dialectics onto situations where they may not fit, in a conscious or unconscious bid to make the rest of the world conform to their standards of how society should conduct itself. Elkins wrote: "A lawyer's way of thinking and representing certain events in the world consists of ... the structuring of all possible human relations into a form of claims and counter-claims, and the belief that human conflicts can be settled under established rules in a judicial proceeding." * What causes so much grief for Bowden is that the plotting of Max Cady mocks the order of a civilized judicial hearing; even Cady's mere presence – debilitating as it may be – cannot be categorized as a measure of claims and counter-claims. Upon arriving at New Essex, Cady breaks no law, crosses no property line. He simply taunts Bowden – following him in his convertible, blowing cigar smoke in his face, buying his family ice cream. Bowden is stunned that Cady can exist and maneuver within the law, when his mere existence reinforces Bowden's belief that Cady belongs in jail, away from society. As the story progresses, Bowden begins to lose his faith in the legal system – not because it favors an ex-con over himself, but because his conflict with Cady stands outside of the normal boundaries of criminal or civil law. When his own helplessness becomes apparent to himself and his family, Bowden feels desperate to act – illegally, if necessary. He asks a private detective to hire three goons to attack Cady, to sway the ex-con to skip town. But Bowden has failed to foresee the obvious legal pitfalls of his action, and so the fight which should have sent Cady running away with his tail between his legs does the opposite: sets Sam up for a humiliating fall. It is a measure of how Bowden has separated himself from his former client, feeling himself superior, when in fact they are both cut from the same cloth, each capable of tremendous brutality. Evidently Bowden may only be able to recognize but not appreciate the lower depths, because his experience as a lawyer has been self-limiting; he doesn't believe that kind of ugliness has any place in his life, even though (being human) it is a small, primal part of him. Bowden's denial of this fact is what cripples him, leaving him unprepared to deal with Cady on his own terms. By the end of the film, Bowden's fears of Cady are more than justified

[Scorsese's prodigious use of blood is proof of that] but that doesn't negate

the spiritual lesson which Cady is determined to instill in him. This is

reflected in Cady's ominous reference to the Biblical tale of Job, in which

a pious man's faith and understanding of himself and his place in the world

is tested in an extreme, cruel manner:

"He may be more of an animal at the end than Max Cady," says Nolte, who recognized upon accepting the role that Bowden was not a heroic figure as typically drafted in Hollywood films. "And maybe that's just something that we deny ourselves in life – we do not accept the primitive man in ourselves. We constantly put up this front of civilization and then are shocked when we find ourselves in war, or that we are war-like people. We are violent people, and we have to come to grips with that. "And the way to come to grips with it is not through denial; you have to assimilate it and transform it into something else – creativity or whatever, you have to channel it. Certainly if you don't come to grips with the warrior inside of you, it'll eat you up. This is one thing that Max Cady knows; he has that wisdom of knowing the lower depths." Being in constant contact with some of the worst elements of society, lawyers might understandably become jaded in their outlook of the world at large. For this reason the legal mask can be a protective device, enabling them (intellectually and emotionally) to stand above the proceedings in order to illustrate the Law's higher purpose, and remain unsoiled by the alleged actions of their clients. And yet, Nolte argues, precisely because of this elevated position in which lawyers operate, they must strive to be even more human, rather than to de-humanize themselves. Because the perceived need for a lawyer mask is often dictated by the crushing demands of an overloaded judicial system, CAPE FEAR can be viewed as an outrage against the temptation to shuffle or plea bargain cases, not always in the best interests of the defendant. "We are questioning the men who run the law," Nolte asserts. "Not the law per se – the law is fine. The law is only as good as the moral character of the lawyer, and there is an extreme problem in our society of men manipulating the law out of convenience, or monetarily. And then we played with that, [suggesting] maybe the only way people grow is to go through [this struggle], that the masks have to be torn down. That power and control really have to be taken out of the hands of the individual, so they can truly see what their interrelationships are." CAPE FEAR attempts to show the damage that a lawyer mask may do, in disguising an individual from himself. It is ironic that, in this film's view, a ruthless murderer can be more spiritually enlightened than the lawyer who deems him unfit for society; ultimately, the moral to be reminded of in this violent thriller is that men on both sides of the law are actually on the same side of humanity.

* from The Virginia Law Review, © 1978. Screenplay excerpt © 1991 Universal Pictures/Amblin Entertainment. All rights reserved.

|

All rights reserved.

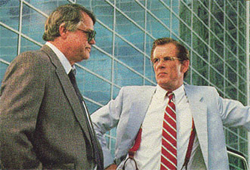

At the start of the story, Sam Bowden, in his mid-40s, wears his legal persona well: he is efficient, cool, in demand. He has built important connections in the business and political sectors of New Essex. Bowden fits into his role with ease and assurance. He is (to recall the metaphor) a chessmaster.

At the start of the story, Sam Bowden, in his mid-40s, wears his legal persona well: he is efficient, cool, in demand. He has built important connections in the business and political sectors of New Essex. Bowden fits into his role with ease and assurance. He is (to recall the metaphor) a chessmaster.