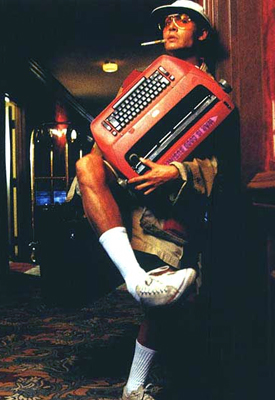

THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // "FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS" (1998) |

FEAR AND LOATHING |  |

|

In early 1998 the Writers Guild of America deliberated upon the official credits which would be featured on the film adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Terry Gilliam (who had replaced the film's original director Alex Cox) had adapted the book with co-screenwriter Tony Grisoni, disregarding the version of the script by Cox and Tod Davies that was originally going to go before the cameras. When the WGA announced that Cox and Davies were to receive sole screen credit, Gilliam protested that his and Grisoni's work had not been validated, and made a rather public demonstration of his antipathy for the credit arbitration process. He went so far as to make a short film to be attached to prints of FEAR AND LOATHING that would inform the audience that what they were about to see was not really written, since it was based upon a script that was credited to nobody. The following analysis of the Gilliam/Grisoni and Cox/Davies scripts was done by this author to objectively discern what, if any, influences the original script had upon Gilliam's adaptation, in order to help determine how much of the final, filmed screenplay was original and unattributable to the WGA-credited authors. This information was provided to Gilliam at his request during his arbitration process. [FYI: The Daily Script Web site had posted HTML versions of the Cox/Davies and Gilliam/Grisoni screenplays.]

There are three basic criteria upon which I believe different versions of an adaptation of a book may be judged. Structural Choices

Adaptation

Original

COMPARISON STRUCTURAL CHOICES The scenes preserved from the book FEAR AND LOATHING were very closely matched by the two scripts, not surprising in as much as they were by and large the main scenes of the book. [This would be similar to comparing two screenwriters' adaptations of GONE WITH THE WIND; both would definitely maintain the burning of Atlanta, but may not both incorporate Bonnie Blue's sucking her thumb.] The scenes selected by both Cox and Gilliam very closely paralleled one another, but in most instances there were changes in dialogue and often in stage direction; some scenes ended in one script whereas their parallel scenes continued further in the other. There was much greater divergence when ancillary characters or sub-plots were involved. The Cox script chose to play up the Innes/selling an ape sub-plot (including an ambulance at the scene of the ape's rampage) which the Gilliam script virtually ignored. The following scenes from the book were used in the Cox script and not in Gilliam's:

The following elements were in the Gilliam script and not in Cox's:

Both adaptors translated the book's newspaper accounts of tragedies and war reports into background radio as a dramatic device, although each script selected different news reports. What is of greater distinction is how emphasis was different within the same scenes. For example, in Cox it is not indicated that the audience would ever see the acrobat act involving nymphettes and wolverines — they may simply be a part of Duke's exaggerated world view; in Gilliam we clearly do see them. There is also a greater emphasis in Gilliam placed on the fact that Duke's voiceover and spoken dialogue often blur — within his own mind and from the audience's P.O.V. as well. Under this first criteria I would say that there was little in common between the two scripts that would not have been found by comparing any other two (or more) screenwriters' adaptations of this same book.

ADAPTATION What is being judged here is which changes in the book made by the first team were kept by the second. The non-linearity of the book (which incorporated flashbacks and recalled memories of Duke, "recorded" events, news reports and "found" transcripts of conversations) was a primary factor to be judged- there was also a shifting of events from within the book's "true" chronological timeline in order to facilitate a preferred dramatic order, or to suit one adaptor's vision of a character. The Cox script was much more interested in presenting a straight time-line to the story whereas no such linearity existed in the book. In this regard the Gilliam version is a more honest retelling of the book. There were changes made by Cox which were not carried over into the Gilliam script; these include:

Of changes from the book made by Gilliam which did not appear in Cox there were the following:

Both adaptors' changes shifted the focus of characters 'in their respective scripts, revealing how different the emphasis was in each script's story. In Cox, Duke was a central victim in a swirling vortex of insane, bizarre and often threatening scenes. His experiences, even his own drug episodes, were to be depicted from an omniscient objective outside P.O.V. His voice-over served as ironic counterpoint to events that the audience saw for themselves. In Gilliam, the audience's P.O.V. was less omniscient and more subjective of Duke's experiences; Duke absorbed the crazy life around him, as much as it may have repulsed him. His interior monologues (voice-over) was less a visceral or ironic reaction to events and more an exploration of what these events meant in a changing society. Of changes in book elements made by Cox which were incorporated in the Gilliam script, there were six:

Of these six, the first four were primarily instruments for compressing time; it is only the last two wherein dramatic emphasis on location and character were shifted from that of the original source material (Duke's admission that he is a D.A. following his escape from Las Vegas comes as an ingratiating fib, not a self-protective mask of paranoia; and his departure via car better suited logistics as well as the "road" aspect of the story). Given the overall length of the script, these changes represent only a minor influence by Cox's script on Gilliam's. In fact, Gilliam's seems closer to the original source material.

ORIGINAL MATERIAL This section will measure original material (created scenes, new characters and invented dialogue) that appear in each script, and how much of Cox's invented material appears in Gilliam's. In Cox, there were the following additions to what had appeared in some form in the book, which Gilliam did not use:

In Gilliam the following new material had not appeared in Cox's adaptation:

Most of the new material in the Gilliam script that was borrowed from Cox was comprised of stage directions that were not explicitly spelled out in the book; there was little invented dialogue in Cox's version, and hardly any of that was reprised by Gilliam. Some of the repeated descriptions and text include:

It appears that whatever new material created by Cox

that was kept by Gilliam was primarily stage directions or descriptive

material, none of which materially altered the narrative, locations or

characterizations, except for the Hardware Barn scene and the introduction

of the CHP officer. In some instances stage directions were kept although

the dialogue itself was altered, so the dramatic focus of the scene might

be different from the first to second scripts even if the staging were

similar.

I believe the Gilliam script, although benefiting from Cox's work in that he had broken much of Thompson's prose into stage directions and voiceover/dialogue (a task Gilliam would otherwise have had to do himself), is a separate entity, in its tone, narrative and audience P.O.V. If Cox's script had never existed, or had never been read by Gilliam, the subsequent Gilliam script would be little different than the present one, except for the closing scenes (the Hardware Barn and Duke's farewell to the Marines) which represent the last three pages of the screenplay.

Postscript: Gilliam ultimately won the battle over credits with the WGA, albeit in an unusual fashion: He and Grisoni received FIRST credit on the script, FOLLOWED by Cox and Davies! Regardless, Gilliam was sufficiently dismayed at the arbitration process, and by the fact that writer-director hyphenates have seemingly less power over receiving writing credits than do screenwriters that -- accompanied by Tony Grisoni -- he publicly burned his WGA membership card (torching his middle finger in the process) outside of a Barnes and Noble bookstore in Manhattan.

|

copyright 1998, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.