THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (1975) |

"Come See The Violence Inherent In The System" |  |

|

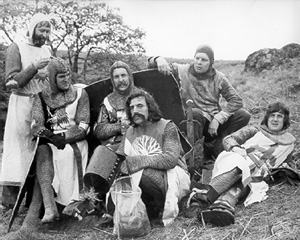

The Pythons' second film, MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL, was funded by rock stars, filmed on a shoestring budget in the wilds of Scotland, and held together by a pair of neophyte directors trying to work around a string of obstacles, from broken cameras to an alcoholic playing the film's most stoic character. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones teamed up to direct HOLY GRAIL, a follow-up to the comedy group's first foray into filmmaking, the sketch compilation AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT. That film (which was, despite its title, a re-filming of bits previously aired on television) was directed by Ian MacNaughton, who had also directed most episodes of MONTY PYTHON'S FLYING CIRCUS.

What was it from your experience with Ian MacNaughton that you thought worked (or didn't) with him directing Python? Well, Ian, he worked only because he put up with things. Everybody pushed him around. I like Ian a lot, I mean just his personality. I liked him a lot. I was always frustrated because it didn't look as good as it should. I mean the lighting wasn't as good as it should have been, all of those things. So in a sense I was constantly frustrated, so was Terry; we wanted it to look like Drama as opposed to Light Entertainment. That's that's what doing HOLY GRAIL was about, 'cause HOLY GRAIL was made to look as beautiful as Pasolini and all that. Because the humor is funnier if it comes out of that kind of believability. If you've got something beautifully lit and the costumes are really great and the set's looking good and then you do some absurd nonsense, it's funnier than having it in a cardboard set with some broad lighting.  And I think especially since a lot of the stuff we would be doing would be parodies of things. So if you're going to do a parody it's got to look like the original. And Ian was really a sweet man, but it was television and you churned it out. That's what we did. And again, we didn't have much in the way of budgets. Then there would be all these times I'd get in there during filming, 'The cameras should be there.' Terry would do the same thing, we were always pushing him around. I think we were just frustrated because we wanted to film this, too. We were convinced we could do it better. Why weren't you doing it from the outset? Because in the BBC it didn't work that way. They would put a producer/director on the thing. That isn't what we were when we started. Well actually, it began with John Howard Davies, David Lean's Oliver, who directed the first four Pythons. And there was a kind of Light Entertainment direction at the BBC which was very sort of sloppy, where it was just, 'We do this, get the camera.' Drama was serious; that's where the real talents hung out. They ate at a separate canteen? It's almost like that! It always felt like that; they had more money, they can light this stuff. But Ian had also worked with Spike Milligan, the Q series, that's why the idea of Ian coming in, we liked that idea. He wasn't forced upon us, we lucked out. He worked with Spike Milligan, great! And Ian held it together, but he would be constantly — Oh, shit, why is the camera on that?' I think anybody would have been beaten up by us in the same way, but he trotted on, he did it. If it had been left up to us we couldn't have done it. There's just no way. We thought we could but I'm sure we couldn't have. And that's why when we actually got around to making HOLY GRAIL, it was like, 'Oh, now we've got to do all the things we claimed we could do that Ian couldn't do.' And I think we did, but within I think it was the end of the first week of shooting, where everyone got pissed one night, Terry and I were just shattered because everybody was going, 'Wrong!' A lot of shit had been dumped on us and a lot of things had happened and we were actually managing to survive and keep things going, and Graham got really pissed one night, just said what a complete disaster we were making — this was a time we were feeling very, very vulnerable! — and how Ian should be in there and what egomaniacs, megalomaniacs, useless pieces of shit we are. Oh, that's great. 'Fuck you, Graham! Get your lines right!' And then really, there was one night I just thought This is horrible, but the one sad thing is deep down I think [we] both felt they may be right, we might not be able to do this. But we got through it.

So how it did come to pass that the two of you ended up directing HOLY GRAIL? Was it, from the start you wanted to direct? Yes, basically yeah. 'Cause Ian had done AND NOW FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENT, and that was the one I think we started pushing even more to be directors. We were really around Ian, Terry and I really had really got him surrounded on that one, so when it came a chance here's the money to make a Python film, we just decided we wanted to do it, we were the ambitious directors, and the others went along with it. Did you think you could both be co-directors? Yeah we did. That was it but Terry and I tended to agree on most things, until we actually started working together and then we discovered we didn't agree quite as totally. And we both had a very similar view of the whole thing, we knew what the look we wanted, all of those things. The real difference came in that I've got a better eye than Terry, is what it's about, I'm better at those things, and he's better at other things. I've got a better eye and ultimately that's how we ended up working it. So we split; I ended up being at the camera, and he worked with the guys, 'cause I having been in my little garret all those years my social skills were not as highly developed as they are now! The idea of out there slogging our guts out and trying to get them to do what was needed for the sake of, 'cause again, John and Graham didn't particularly like it, Eric was all right, they didn't like all this cumbersome stuff. I mean they just want to go out and do the funny lines; that's a bit extreme but it was kind of like that.

'This is really uncomfortable, Terry.' 'I know it's uncomfortable but if your head goes above that I can't do the matte, blah blah blah.' 'We can't act like this.' 'Well, I need another five minutes, we're not quite set up.' 'These things are killing me.' 'Shut up!' Oh fuck. 'This is your fucking sketch; you wrote this fucking thing, I don't need this!' And I walked off. That was the day I finally cracked, and I went off in a huff and lay there in the grass: 'I'm not going to do this shit.' It was appalling behavior! I left Terry to take them on. I think that was probably the time I finally, I don't want to have to sit here and have to beg you guys to do this so that your sketch that you've written works. I don't want to sit there and have to tell you how all this stuff and why, I'm doing it because I need your heads below the battlements. It was really difficult for me because having only had to deal with pieces of paper, things like that, to actually be able to convince people to do things (which you have to do as a director) was really, I don't, my skills were not at all, and so I was pathetic. But I mean, the look of the thing and all that, was great because we could keep on that. I mean, Terry and I disagreeing, it wasn't big things but purely practical things. The camera should go here because that's that. Terry goes, 'Why don't I go over here?' 'Well, I think it should be there.' 'Well, I want it there.' 'Terry, the shot's better here.' 'Eeeuughh ...' He actually did it to me on JABBERWOCKY. In the beginning he's the poacher, we're sitting on Burnham Beeches, and I've set this crane up, it's what he's pulled up off the ground. I set the crane up where we're going to do it, it's a cherry picker, takes a while to set up, and the sun is going down, and we got to get it before the sun's, I wanted long shadows to help define the difference. And Terry, 'Eeeuughh, there's a little place over here that I think might be better.' Terry's very persuasive and John Goldstone said, 'Well, Terry, why don't you just move the crane?' I said, 'If I move the fucking crane we're going to lose the light.' Terry says, 'Eeeiighh ... ' Fuck! 'Move the fucking crane!' (just to show them). So we move the crane, we get in there and it doesn't work there! Now I've got to move crane back, so I proved my point, lost the light, all this because I know I'm right because that's what I'm good at, but I don't have the time or patience to explain exactly why the shot is better here.

It sounds like John manipulating. But Terry doesn't manipulate. With John it's him trying to pull strings like a puppet. Terry does it just sort of sheer, his gut is telling him, his passion, his enthusiasm, and I'm always a complete sucker for enthusiasm. When somebody is so enthusiastic and so convinced of something, I tend to think that's probably a good way to go. But what was happening on GRAIL, these things, these enthusiasms I knew weren't right. Now this may sound wrong, but I just know when it came to where the camera should go, and certain technical things, that's what I'm good at. And I find trying this other way — 'Eeeeaugh, might work!' — is wasting time, we don't have the time to do that because the light's going down, we're going to lose that and the shot will fall apart. And so that's really where we divided in a sense, and because I couldn't stand talking to the fucking group, to try to convince them to do anything my way, so Terry and I split — and it worked out very well, we plowed on, because they I think they always deeply suspected me of being more interested in the image than the comedy, that was the basic thing — John in particular just thought everything I was doing was getting in the way, because the comedy for him it had to be comfortable and easy and then it would flow, and I was always trying to stick a helmet on him and this and then stand in a ditch and that was getting in the way. And none of them, I mean they'd all been involved in those, but they're kind of pretending that you don't have to do all these things, and I think you do. That's why when I went to do JABBERWOCKY, it was great — all these great British comic actors, the best of the lot, who all just did what I told them to do, without complaining! And we made the thing look great. And I just want it to be both great-looking and funny. Not great-looking. I want it to be both things.

When you did LIFE OF BRIAN, how did you decide not to co-direct with Terry? Just because at the end of HOLY GRAIL, no it was JABBERWOCKY that spoiled me. I got through HOLY GRAIL and then done my own film, it was, I just don't want to do it, I don't want to get into arguments with Terry about we should be doing it this way we should be doing it that way. I thought let me just design the thing. Again it was like going back to being at the camera. Because on HOLY GRAIL that's what I did anyway as well, I mean the whole look of the thing was just stuff I really concentrated on. And so I did the same thing with LIFE OF BRIAN, but unlike GRAIL where as a co-director I was in control of where the camera was, as a designer I wasn't, and so I became the resigner at that point! I mean, you can have all this stuff, but if you don't put the camera there you don't see it! I don't mind if you don't want to put the camera there, but if we built all that stuff and spent all that money, put the camera there! And it got, I got a little bit crazed about it as well. I think working with the group was making me fraught, because it's one thing to be crazed on your own project where you're just pushing everything where you really got control over it, but the group thing was just for me becoming more and more difficult. It's like the writing on the wall, Romanes eunt domus. Now all that's set up to be shot as a day-for-night shot, it was supposed to be night. And John got out there and the camera needed to be, to do day for night you've got to point the camera in one direction as opposed to the other direction so that you basically you got to be front-lit so that you can crank everything down and still have light on the faces, the sky goes dark. And John didn't want to do it that way, he wanted to hold his sword in the other hand, and so he couldn't do it left to right, he could only do it right to left — whichever, it doesn't matter. And so Terry sticks the camera so basically you got the scene and to get it looking like night, you've got to drop it so down so you're missing a lot of stuff in the eyes in John and Graham, but basically it doesn't look like night, either, because they couldn't bring the sky down enough. I go crazy with things like that, and I'm glad I wasn't directing because I would have just exploded at that point, but Terry, 'It'll be fine, put the camera here,' he didn't have the problem that I would have had.

It's this idea that the Romans were determined to put order in this place no matter how chaotic this Jewish city was. And this building going on, and it's really, we did all this stuff, it's the problem of doing it all and designing it and building it and not spending that money elsewhere, and then the ceiling is this incredible ceiling which cost a fortune to do, and then Terry shoots it like a television series boom boom boom like that. Straight on and flat. Now, it's a brilliantly funny scene, you don't need the other stuff. Except that if we'd decided at pre-production meetings and decided to do all that other stuff and go along with it and then not use it, makes me crazy. I probably have the same effect. No, I don't actually on designers on my films because I don't waste anything; if we've spent the time doing it I'm going to get that fucking stuff on film somehow!

So of course when Terry gets in there with the camera and tries to see the angle he can't do it, so now he's got to dig a hole in the ground to get the camera where it belonged. It's spatial relationships, and ... I don't know. [laughs] It's awful, you know. That's why I just can't get involved directing the group. This stuff is too important to me to just take it easy. And Terry's more lax, lax in a strange way, it's less important to him. John is very happy, he didn't want to wear any beards in the films, it's like that, so he just puts on the skirt and that's it and he's happy. And it goes on and I felt, that's one of the things, with me being Jailer and some of these other characters, it was a way of getting texture to the movie, so I cover myself with mud, I do anything to try and build up a sense of reality. Yeah, build up this real sense of reality and a world going on around it.

But do they appreciate it afterwards? Do they look at the film after the fact, look at a shot and say, 'Yes, it's funnier because you held out for it'? I don't know, nobody's every said anything! [laughs] Not that I, I've never sat down and really talked to John. I mean, Eric understands it, and I think Mike understands it. I don't know, that's what's so funny about us as a group: we've never sat down and discussed things like that. We don't spend a lot of time congratulating each other and patting each other on the back, which is the good thing. Not a lot of time spent criticizing, playing Monday Morning Quarterback? We do, I think we're very critical, so that's good. I just always felt there was sort of a shared respect, that was the main thing, which was sort of unstated but it was there. And that's when the group worked best. Like, I love LIFE OF BRIAN, I think it's great even though it doesn't have visually as much beauty as I — or not just beauty but interest, things in there. But it's fine, it doesn't matter, it's not that vital because I think there's enough there, there's enough sense of it, to be really good. Because ultimately in that instance I felt what we were saying was what was important, the ideas were really to me the great thing in LIFE OF BRIAN, such funny ideas, such really intelligent, again outrageous and strong and smart ideas: the shoe sandal, the heresies involved, whatever that sequence is 4 to 5 minutes, we covered the entire history of organized religion. It's wonderful in a sense, this is brilliant.

And so it's like the crucifixion, we went out there and Roger Christian and I we went out to Matmata. Terry is so excited and so he's convinced the crucifixion scene is going to be out there. So rather than waste time we'll split up, we'll go in two separate areas. He gets in a car and goes roaring off that way, Roger and I go this way. We find this spot that's fucking great; it's got everything you want, not only this beautiful ridge but there's a range of mountains behind it, the sun will be at the right angles for doing everything, and in front of the hill, on the front part of that there's like this huge opening with, it's like golgothic it should really be, it's like an Acropolis there, so you've got all that working for you, and the sun will be perfect and the mountains, everything would be perfect. And so we come back and Terry I can see has not found what he's wanted, he's disappointed, and we decided we've got to be really careful how we present this. So I go, 'Okay, we found something that might work, we're not sure.' We were walking on eggshells. We go out to this thing and say, 'Well, what do you think?' Terry said, 'Hhmmm, yeah ... Oh! Look at that over there!' And it's in the wrong place! And that's where we shot the fucking thing, we shot the crucifixion in the wrong fucking place. Aggh!!!

He would just not accept that Roger and I, and he didn't want to, when we said the light will do this, and sort of halfway through this explanation, because Terry had to find it. It was at that time, he had to find it, it was this competition, he had to get it. And he found the place and it's the wrong place! And it's fine, the film goes on, and it ends, all that's fine, but there's a better place, it would be such a spectacular end to the film. [laughs] So Roger and I go, 'Oh, fuck!' So what do you think his strengths are as a director? I think just great performances, his comic sense is spot-on. But does he have a special quality for directing the Pythons, as opposed to getting an outside person? I think yeah, I think so because he instinctively understands the material, he understands what's right and wrong, what's needed and what isn't in that sense, and he works really hard, he badgers and he just keeping going on, and that's what after HOLY GRAIL I said the director's job is a dogs' body job on this, because we were running around doing all the work for them? The other half of the group? It actually started to create a kind of split in the group because there was Terry and me over here and there was them, which I don't think really was a great moment. I mean after HOLY GRAIL where we did the first dub of it we showed it, there was like Pink Floyd and Elton John, a few people turned up and the backers and all the other people, and I can't remember whether it was Eric, I think Eric walked out, he just hated seeing what WE had done to ruin the film, he stormed out. I can't remember if Graham did. It's like, Jesus! And Terry and I were getting the blame for it, for fucking up the film, and that wasn't a good time. It all got sorted out, but that was a kind of worry in a way, maybe in a way with just Terry directing [the group], it became, it was so uneven you couldn't just blame Terry for it, everyone had to be involved in it more, but with Terry and I together it was like this little unit moving around. Terry's got so much energy, I think he's got more energy than I do, he wakes up in the morning (claps hands together), 'Let's get to work!' this smile, he can't wait to get going! And I'm just like, 'Oh, fuck, here we go, another day,' have to drag myself into it. And I think because again with performances and that sense of 'Let's do it!' is very good where I am going to take longer setting up a shot, it's going to take me longer to get all the elements right and get the smoke and then because I'm always adding elements to the thing, where Terry will deal with two or three levels and I'll be going through six levels of stuff, complication, and that's much better for Python to work that way, at that pace. So I mean Terry's the right director for Python. I think in a sense it was more about me learning that I wasn't than anything else. Because I don't think I've got the energy to fight the group as a director. I have the advantage when it's my film being the director, I don't have to fight, and it makes it easier, then I can work with like-minded people that seem to appreciate, no they don't actually appreciate all the things I appreciate but they appreciate that bit that they're working on as much as I appreciate that bit. That's what I like about what I can do in films because I know a lot and I've just sort of taught myself in every area so I can deal with it, and I find that Terry gets interested only so far in these things. So by concentrating on the immediate thing, I think it's the right way to go. If you can then surround himself with really good people who are doing their stuff, because I for me being the designer it's like I work with the director, what the hell you can't work for anybody, it's no good it doesn't work that way. Because what I actually do is try to work for the film, but that may not be the same thing as working with the director. But the way it's worked out is the right way. And everybody's happy, because again Terry's got more patience than I do as well with them. I've got patience with all the stuff, but them? I really run out of patience! Is that part of his competing with the other members of the group, that he is going to show them that he can put up with them? I don't think so, I've never quite felt that. I've always felt there's more of a competition between Terry and me. It's just that he's so passionate about, so enthusiastic about it, and no, I don't know if he feels he's competing with the others. I mean, he still obviously got that sense of him certainly he's right, but then I have the same thing, John has it, we all have it, most of us. Mike is more malleable, Graham didn't seem to care as much. That's what's so extraordinary: You've got six egos that are all pretty strong and all yet working together which astonishes me, it still gets me. Shit! And it always came down to that fact that we all thought each of the others was brilliant. You may have hated him, but they were brilliant!

| |||||||||||

copyright 1998, 1999, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

But we were lucky. The BBC was a great training ground for people, for make-up, for costumes, sets, all that stuff, and people really liked working. We were lucky we could get good people working with us, Hazel Pethig who did costumes on HOLY GRAIL and BRIAN and then A FISH CALLED WANDA, JABBERWOCKY, if you look at the [Python] shows, the costumes are much better than the sets and they're certainly much better than the lighting, and we were lucky there. Maggie my wife was doing make-up on it and several other people who went on to win Academy Awards and things were being honored, you're really working with a really good group. That's the pity of the BBC now, they've given that up, everything's farmed out now. And it's really sad because they trained the best people in England, the BBC. With modern accounting methods, the BBC doesn't feel like it should be training the nation, it should just be in getting ratings and balancing the budget. It was a training ground for incredible talent in this country and it's all gone now. That's the sad thing about England what Maggie Thatcher did, parceled it all out to different accounting everything's and in the short term it works just fine but the long-term I think one's finding already the talent on a technical level is not there as it was once. Because of the way the BBC was now changing. We always felt the BBC people would get really good and then they'd leave and go to ITV and make more money. That's not totally fair to the BBC; it's a public institution, people are being taxed for the thing, blah blah blah, and that's fine, they're doing public service as well on many levels, but that's over.

But we were lucky. The BBC was a great training ground for people, for make-up, for costumes, sets, all that stuff, and people really liked working. We were lucky we could get good people working with us, Hazel Pethig who did costumes on HOLY GRAIL and BRIAN and then A FISH CALLED WANDA, JABBERWOCKY, if you look at the [Python] shows, the costumes are much better than the sets and they're certainly much better than the lighting, and we were lucky there. Maggie my wife was doing make-up on it and several other people who went on to win Academy Awards and things were being honored, you're really working with a really good group. That's the pity of the BBC now, they've given that up, everything's farmed out now. And it's really sad because they trained the best people in England, the BBC. With modern accounting methods, the BBC doesn't feel like it should be training the nation, it should just be in getting ratings and balancing the budget. It was a training ground for incredible talent in this country and it's all gone now. That's the sad thing about England what Maggie Thatcher did, parceled it all out to different accounting everything's and in the short term it works just fine but the long-term I think one's finding already the talent on a technical level is not there as it was once. Because of the way the BBC was now changing. We always felt the BBC people would get really good and then they'd leave and go to ITV and make more money. That's not totally fair to the BBC; it's a public institution, people are being taxed for the thing, blah blah blah, and that's fine, they're doing public service as well on many levels, but that's over.

The one scene where it blew up was the scene when all the animals were being thrown over the battlements, and to do the shot I had to get their heads below the parapets so that I could do a matte to put the animals in the [shot] and that meant digging a hole in the ground and sticking the camera in the hole and they had to be on their knees, so everybody was the right height.

The one scene where it blew up was the scene when all the animals were being thrown over the battlements, and to do the shot I had to get their heads below the parapets so that I could do a matte to put the animals in the [shot] and that meant digging a hole in the ground and sticking the camera in the hole and they had to be on their knees, so everybody was the right height.

And I think most of the stuff we pulled off in GRAIL worked really well, I think we did it. I was just looking at a little clip this morning, the 'Bring out your dead.' It's stunningly beautiful, it's gorgeous. Shit has never looked so beautiful! Muck! And it's funny because of that, it's funnier I think because it feels so much of a serious movie, a real movie with real people groveling in the mud, and then, 'I'm not quite dead, I'm feeling much better!' It's funnier that way.

And I think most of the stuff we pulled off in GRAIL worked really well, I think we did it. I was just looking at a little clip this morning, the 'Bring out your dead.' It's stunningly beautiful, it's gorgeous. Shit has never looked so beautiful! Muck! And it's funny because of that, it's funnier I think because it feels so much of a serious movie, a real movie with real people groveling in the mud, and then, 'I'm not quite dead, I'm feeling much better!' It's funnier that way.

And things like in the Pilate scene, one of the funniest scenes in the movie where Michael, that set is an extraordinary set, and we spent a lot of money on it, and you don't see it. It's just me and the way I like working, I don't like wasting, I hate wastage. I said, if we sit down and talk how we're doing the thing, we've done this, that, we've got all these ideas, because the set was actually quite funny. It was an idea in the set, it wasn't just a room, it was an idea, and the idea is not on film — not that it's an essential idea to the film, but it is an idea. It's about the Romans coming in and carving up this sort of Jewish labyrinth and plunking down this atrium in the middle of it, and in a sense it's very funny because you've got three floors, this wall which hadn't been tidied up yet, and the atrium is two floors, and nothing is quite working in that room.

And things like in the Pilate scene, one of the funniest scenes in the movie where Michael, that set is an extraordinary set, and we spent a lot of money on it, and you don't see it. It's just me and the way I like working, I don't like wasting, I hate wastage. I said, if we sit down and talk how we're doing the thing, we've done this, that, we've got all these ideas, because the set was actually quite funny. It was an idea in the set, it wasn't just a room, it was an idea, and the idea is not on film — not that it's an essential idea to the film, but it is an idea. It's about the Romans coming in and carving up this sort of Jewish labyrinth and plunking down this atrium in the middle of it, and in a sense it's very funny because you've got three floors, this wall which hadn't been tidied up yet, and the atrium is two floors, and nothing is quite working in that room.

It's like the scene where Ben is hanging in his cell. Roger Christian designed this set, it was a really good set; Ben is hanging way up there and he's just under a sewage outlet so sewage is dripping on his head the whole time, and he's way up there and so Brian's down there, so it's not like they're level. And it was one day, Roger had done this thing and I said, 'This is great," and we'd gone through it, done it up, and then Roger took Terry to the set and Terry says, 'Well, he's going to be too high.' And it was my mistake for not being there. But it was, it goes on and on, and Roger says, 'Oh, fine,' and so he then chopped the whole thing down and cut it down, lowered Ben.

It's like the scene where Ben is hanging in his cell. Roger Christian designed this set, it was a really good set; Ben is hanging way up there and he's just under a sewage outlet so sewage is dripping on his head the whole time, and he's way up there and so Brian's down there, so it's not like they're level. And it was one day, Roger had done this thing and I said, 'This is great," and we'd gone through it, done it up, and then Roger took Terry to the set and Terry says, 'Well, he's going to be too high.' And it was my mistake for not being there. But it was, it goes on and on, and Roger says, 'Oh, fine,' and so he then chopped the whole thing down and cut it down, lowered Ben.

So it just became too frustrating so I just had to step back. There's one bit that I did go down and shoot, that was the opening scene with the Wise Men coming into Bethlehem and they come in, then we go into the set inside and that's Terry, and then we come outside [and] see the Holy Family, that's me, and they're really beautiful shots! [laughs] And it's just that difference; that's what I am trying to do, and I know the rest of the group is not wanting to work, they're not interested in working at that level. And for me to do that takes longer; it takes this, that and the other thing, so it's better that I just step back from it.

So it just became too frustrating so I just had to step back. There's one bit that I did go down and shoot, that was the opening scene with the Wise Men coming into Bethlehem and they come in, then we go into the set inside and that's Terry, and then we come outside [and] see the Holy Family, that's me, and they're really beautiful shots! [laughs] And it's just that difference; that's what I am trying to do, and I know the rest of the group is not wanting to work, they're not interested in working at that level. And for me to do that takes longer; it takes this, that and the other thing, so it's better that I just step back from it.

And there's a weird, I suppose, competition between Terry and me, and that's what's funny it's always there, and maybe it shouldn't be, because I think in a sense we seem to see things in the same way but how we get there is different, because I'm much more technically adept at getting the idea, the image of that idea on the screen, more so than Terry is, and yet I feel he's still trying to compete at that level rather than just accepting that's what I do better than he does, and I can't a patch on what he can do.

And there's a weird, I suppose, competition between Terry and me, and that's what's funny it's always there, and maybe it shouldn't be, because I think in a sense we seem to see things in the same way but how we get there is different, because I'm much more technically adept at getting the idea, the image of that idea on the screen, more so than Terry is, and yet I feel he's still trying to compete at that level rather than just accepting that's what I do better than he does, and I can't a patch on what he can do.