THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // "THE FISHER KING" (1991) |

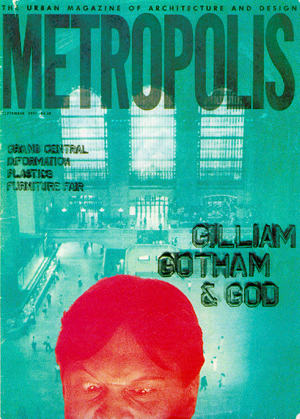

Gilliam, Gotham & God |  |

|

Terry Gilliam cannot be mundane, not matter how hard he tries. It is the director's grand visual style which most audiences take away with them; because the images on screen are so dense, the stories cover so much territory, many of the subtleties that he draws out from his actors are only glimpsed on a second, third or fourth viewing, peeking out from behind a curtain of fireworks. Yet even at their most simple levels, Gilliam's films reveal a sensibility that likes to ridicule and condemn what might be seen as crimes against the natural order of the universe: hypocrisy, aggression and Man's prideful arrogance over all with whom he shares the planet. "I'm just bothered by the basic attitudes about the way people deal with the world," he says. "It's out there ticking away really nicely, and providing all sorts of goodies that people seem to ignore — they're too busy building things, that they can say, 'I did this!' " The drive to build is partly what makes a city, yet a Gilliam city is often defined by how it is destroyed, or rebuilt against its original design. His urban settings reflect the deepest desires and fears of their inhabitants. They are themselves major players in his stories, shaping — sometimes threatening to obliterate — the central characters, even occasionally steering the narrative. At times these cities and the events that take place within them may be at odds with logic and the demands of physical laws, but they always speak truths — usually unsettling ones. While his humor may be either broad or biting, Gilliam's worlds are never simple. A recurring theme is humankind's vain attempt to subjugate Nature with destructive machines and repressive regimes — an endeavor, in Gilliam's opinion, always destined to backfire. His set designs express his viewpoint with tongue-planted-firmly-in-cheek: an elegant restaurant is infiltrated by massive, Stalinesque heating ducts; a Gothic hall is constructed from giant Lego blocks; sleek, Post-Modern furnishings look more like prison furniture than the trappings of wealth.

Part of the results of Gilliam's working method, what he calls a magpie approach ("Having a central idea works like a magnet; things just start sticking to it"), are messy, intentionally so. His worlds are not sterile; a clean white corridor would not exist in a Gilliam film unless it were stained with a drop of blood. And of course it may be taken to extremes: JABBERWOCKY's collapsing medieval castle — thick with dust and excrement, and burdened with overcrowding, ineffectual leaders and unscrupulous businessmen — could stand for the modern world, which has forsaken Nature's beauty for profit and left in its wake an infrastructure too weak to support itself; likewise BRAZIL's messy, bureaucratically-suffocating society, where nothing works properly, and aesthetics have lost a war of attrition to the functions of plumbing and pneumatic tubes. But his attacks on technology are also a cry for Nature, and against the abuse which is heaped upon the earth by those who should be safeguarding it. In the dream sequences of BRAZIL massive windowless skyscrapers thrust out of a serene countryside and blot out the sun. But the 'real,' waking world of the film's protagonist is no less forgiving of Nature: miles of advertising billboards along a highway hide the desolate landscape beyond from one's view, or cheerfully prescribe feel-good messages amidst destitute or condemned surroundings. Even in his Baroque epic, THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN contains the same passions about the man-made mentality. When the Baron flies to a lunar city ruled by an egocentric, calculatingly intellectual King who is convinced that all of the universe is the creation of his own feverishly active mind, we find the place to be cold, empty, artificial and flat. These settings are not always destructive of the central characters,

but they leave their marks on them, and often steer the narrative —

not always where the characters wish it to go.

Born in 1940, Gilliam grew up in a rural community in Minnesota before being transplanted to Los Angeles as a teenager. After fluttering between New York, Europe and California, working on magazines and at ad agencies, Gilliam finally settled in London in the late Sixties, at which time he forged ties with his future partners in "Monty Python's Flying Circus." He provided animated sequences for the troupe's TV series and films, and co-directed with Terry Jones MONTY PYTHON AND THE HOLY GRAIL (perhaps the most authentic-looking film of Arthurian England, even though it was a farce). He also designed "Life of Brian," and for the Pythons' last film together, "The Meaning of Life," he contributed an outrageous short film about ancient insurance clerks battling like pirates against corporate financiers. While Gilliam's films away from Python — JABBERWOCKY, TIME BANDITS, BRAZIL and MUNCHAUSEN — are noted for their wild designs and special effects, the stories each hinge on clashes between unyielding or oppressive social orders and the efforts by a visionary few to break through calcified modes of behavior and thinking. This attitude clearly infiltrates his life as well as his work, since Gilliam has often painted himself as one of the visionary few battling the unyielding or oppressive constraints of the Hollywood studio system. Despite his track record, which had accorded both mainstream success (TIME BANDITS is one of the most successful independently-produced films ever) and critical accolades (BRAZIL was included in American Film Magazine's list of the decade's top movies), Gilliam is only now winning over nervous studio executives who confuse his elaborate visual style with over-indulgence — a sin in Hollywood, though a widely-practiced one. Gilliam's latest film, THE FISHER KING, has provided the ex-patriate his first excuse to work in the States since moving to England over twenty years ago. Underneath the fairy tale romance is a familiar tale of clashes, this one of two worlds sharing Manhattan Island but in point of fact miles apart. Jack Lucas, a successful, brash radio deejay (played by Jeff Bridges) suffers a spectacular fall from his high-profile life at the top, bringing him into association with fellow street denizen Parry (Robin Williams). A disturbed homeless man, Parry is given to visions of a New York both idyllic (as a medieval setting filled with magical, heraldic romance) and horrendous (as a battleground against a ghoulish phantom on horseback). Parry's unrequited love affair with wallflower Lydia (Amanda Plummer), and Jack's unsure relationship with Anne (Mercedes Ruehl), are played out in more intimate fashion than has been evidenced in Gilliam's previous work; there are more close-ups of actors, and the deeply-detailed backgrounds are not kept on screen as long as in, say, MUNCHAUSEN. But New York is clearly depicted in an unusually eccentric way, playing up the city's architectural diversity and capturing it with disorienting or intrusive camera angles and lighting. Capitalizing on medieval elements in Manhattan architecture, Gilliam's locations, sets and costumes appear deeply influenced by the works of Bosch, Goya, Piranesi, Dante, Durer, Claes Oldenburg and anonymous manuscript illuminators. Exuberant, elegant, perverse and scatalogical, THE FISHER KING as envisioned by Gilliam celebrates New York at the same time that it kicks it in the ass.

Morgan: As you've come back and visited the States over the years, what changes have you seen in New York? Gilliam: I actually thought New York had gotten to be quite a jolly place. I don't know if that's a product of having money now, rather than being poor in New York, where I can actually stay in nice hotels, go to nice restaurants and see the good sides of the city. That may have a lot to do with it, because when I lived there, I had no money at all. You feel you're at the bottom of all those great towers the whole time, and everybody else is up there having a good time except you. The streets were where you were left. I didn't actually like the streets because I in my heart of hearts wanted to be up in the top of the towers. The streets, I mean they were lively but when you're trying to get away from them they're not as interesting as when you just submit to them and allow them to take over. When you aspire to those towers, once you get up there, it's the world that Jack's inhabiting on many occasions; you've lost yourself in the process. So you have to clamor back down onto the streets. Yeah, that's where I feel happier now. At least there are people down there, cause it's all about humanity. And the higher you get, the more isolated you get, the more separate from humanity you become. And again you get lost in yourself, you become isolated within yourself. And that's a part of what FISHER KING is certainly about. You have portrayed the modern aspects of a city as being antithetical to social interactions. For example, in TIME BANDITS, in Ancient Greece we see a very social place: people meeting and talking at markets, craftspeople making things, activities, banquets. But in BRAZIL you hardly ever see people in social situations, and when you do, they behave terribly awkward and evasive — they barely acknowledge one another on the street. They're almost hiding from other human beings. In the case of BRAZIL it's because it's a terrorized society, and whatever that terror is, whether it's terrorists or just the complexity of a system that just blows up in your face the whole time, the best way to survive it is just staying in your own little cubby hole. And even that can be terrifying because your own home might revolt against you, as Sam Lowry's does. Yeah, I know, that's the problem with it. Modern life is designed to separate us much more than it used to; it's not the Village any more. We all have our little boxes we live in, and we've got the television that is our communicator. Television sits there and tells us what's going on in the world, what the world's like out there. We walk out on the streets with all these ideas presented from television, and it colors your perception of the world and your reaction to it. That's one of the reasons I live in Europe; I think that European cities — because their civilization is an older one — they've held on to more direct communications, a more direct way of working and dealing with people. The cities haven't become totally dominated by these great monoliths. It's funny that Man builds these things. I don't know if he builds them because he's aspiring to get higher and higher and closer to God, or more like God but not closer to Him; it's probably direct competition to Him. Trying to beat God at his own game. Yeah, your basic hubris. Towers of Babel, Icarus, all of that. I think they want to find out not what God is like; they want to compete: `I'm as big as you, buster!' That's very American. Yeah. I think it's Man, it's always been going on. I think other, older societies have built their Towers of Babel and then fallen on their face, and they've gotten used to it. And America, being a 20th Century nation, a place where modern technology can do its most work — or damage, whichever — it gives Man incredible powers he never had before, and that's the way it goes; he builds faster, taller, everything. He's got more ways to keep everybody at bay. And it really worries me. One thing I do like about New York, you're in the life on the streets. But I used to like it when you got down to [Greenwich] Village, places like that where it wasn't a grid — the grid drives me crazy. With a grid of streets there aren't surprises, you've got a vista that goes forever. When you're down in the Village you've got curves and twists and so on, your view doesn't go further; it turns the corner and there's a building there that stops you. And if you're on 43rd Street, you know the next street up is going to be 44th. That also, yes. You're victim to the limitations of numbers. Everything is defined. I hate this idea of numbering the streets like that. Streets have got to have names. Getting from A to B [in Europe] is not as simple as getting from A to B in the States. A to B in the States is a straight line. One of the things I like about Europe is, going from A to B you have to meander — the quickest way from A to B is meandering. And if you're meandering, things happen. I think the meandering approach of Europe is much healthier. The way Los Angeles works, it's a series of oases, and people rush from one to another and try to get through the bits in-between as quickly as possible and have nothing to do with the bits in-between. So you get on the freeway, zip, boom, they're there. They miss out on chance encounters or something that diverts you from your immediate goal. I mean, L.A. even got rid of the streets! You just drive right over the streets now. You get in your car, your capsule and zip! As fast as you can to the next thing where you know somebody. I've got a place in the country in France, a little farmhouse which I really love. And I hardly ever get there, but the fact that it's there is really important to me. I know I can get there, I know I can always escape back to the country. But unfortunately I find that the city fuels me all the time, and I think just so much of what I do is based on anger and frustration and confusion and trying to deal with these conflicting things, you know; when I get out to the country I get very placid and calm and boring and non-creative. How long a stretch can you go in the country? I don't know, a few weeks. But it refuels me in a different way; that's what I think is important, is that if I just was within the city the whole time it would drive me crazy. I think it means just dropping back to something much more basic and simple. We didn't have electricity for years, cause I didn't want electricity. In the end we got it because I wanted a fridge to keep the drinks colder. But what I loved without electricity, at night walking around the house with lanterns, the shadows are shifting all the time; the place becomes really wonderful. Wherever you go the light's shifting and the shadows, everything's twisting and turning; it makes the place a moving kind of place; it's not a fixed, rigid house. And with electricity it is. The light sources don't move, and there it is: a rigid thing. And I find in France I sit and watch the fire, and it's infinitely interesting. These are ancient things, but the thing about them is they work; it's not that anybody was very clever, it's just that our cleverness creates all these other forms of entertainment and distraction, but it's hard to beat a fire. I'm trying to work on a thing on the gods of the city. Because at least the old gods were streams, rivers, lakes, trees, stones, all the things that make up the world. And we've created these cities, which are all man-made, and I'm not sure what you worship there; I suppose you end up worshipping Money, another creation of Man, because you've got to have one god or another to deal with. So it becomes Money, and Position, and Career. And then there are those who worship at the alters of Culture: Theater, Abstract Expressionism, whatever. And these are things you can then dedicate your life to, but they are all basically Man-made, and so they're all insular in that sense, rather than just going back to the things, the earth itself, which is the thing that really does support us. It's this constant fight that's been going on for millennia, of Man trying to establish his dominance over Nature rather than the other way around. I think most other animals don't spend their time doing that, they just get on with it. That's why I think we're, maybe we're just one of those unfortunate dead-ends of evolution: Nice try, but it didn't work. Well, you have shown revolution in reverse, in THE CRIMSON PERMANENT ASSURANCE, where an old, Edwardian-era building filled with ancient insurance clerks sails to the glass towers of Wall Street to lay waste upon them. It's a romantic idea that these little old guys can take on these modern monsters. It's a bit like Saddam Hussein taking on America; it's a foolish, romantic idea. And I sort of give them their moment, and they defeat them, but in the end it's a silly idea and they fall off the edge of the earth! Because it doesn't really work that way in the real world. What do you get the most out of living in London? And has that changed over the years from when you first moved there? I love architectural diversity. I like architecture that gives me a sense of a very long continuum. I like reducing my role in the world to being something just on a long pathway, rather than being the center of everything, which I think happens here. And when you're in a place like London, around you constantly are 17th Century buildings, 16th Century buildings, 12th Century buildings! You know it's been going on for a really long time. People have been doing things and building things, and then I look at what I have done, and it seems to be, you know, a little pin prick compared to what other people have done over the centuries. And I like that; it keeps putting me in my place. And I love the juxtapositions of 12th Century buildings next to an 18th Century building next to a 20th Century building. Or in Rome, where there are buildings older than rocks. I love Rome even more than London possibly. That's what was great about making MUNCHAUSEN; I wanted to be able to spend time in Rome. And I'm right now in the process of trying to buy a house in Italy. I keep moving further east. Unlike `Go west, young man,' I've been going east all my life. Mister perverse! And I keep heading back for older and older cultures because I think there's a lot to be learned. America has done the terrible deed of getting rid of history, I really think it has. They refuse to acknowledge history. Uh-hmm. America has gotten rid of it. They just knock it down, put up something new. And it drives me crazy. I mean in London again, when you walk past these places, you're really affected by the aesthetics — it's all around you all the time, and this affects you in a very healthy way. And it just reminds you that there have been a lot of people out there before me!

What is the history of the 17th Century house you live in, The Old Hall? Actually the 15th Century originally, and in the 17th Century the house, where Francis Bacon died, was divided, part of it moved to Highgate Village and reassembled there. Then in the 18th Century it was refaced with a Georgian front. And then at the turn of this century an addition was made; the ground floor room that had been originally in a house in Great Yarmouth that was used by Oliver Cromwell, was dismantled and reassembled in this house. It's a room that's dated 1595; wonderful Tudor-panelled rooms, incredible plaster ceilings, very ornate vines and fruits dangling off the ceiling, and it's got this amazing overmantel piece. It's just amazing, just sort of figures wrapped in wooden shields. It's really sort of a display of the carver's skill, not for any other reason other than showing off. Then another room up above that came from another Jacobean room from a manor in Yorkshire. People like Margaret Rutherford used to live there. And then we moved in, and what did we do to it? I hope we put it back to something beautiful. I mean, I came in there with lots of bright ideas that I was going to do this, that and the other thing, and be very clever with the adapting of the house, and in the end, you have to listen to the house. You can come in there and say `Wow, this is what I'm gonna do,' and get yourself some smart architect and together you design something very clever and witty using the old and the new, or you let the house talk to you a bit. And we ended up doing a lot less clever work than we originally planned because I think it was in violation of the place. The people who were there before you spoke to you? Well, they spoke through the house, whatever they'd done to the house; it had been sort of an organic growth rather than wam-bam approach, and I like that. That's probably why I've always liked medieval cities in particular, places like Rome. They're just a series of accretions: things growing on other things, being altered rather than being torn down and replaced with something new. That kind of organic growth of a city is what I really like, cause it's both totally surprising and utterly human, because you can see each time somebody's gotten a hold of something and done a little more fiddling with it. There is clearly a conflict between a modern world imposing itself upon people, and the history of a city trying to be remembered. In THE FISHER KING, in the early scenes which show Jack in his disk jockey environment, modern New York, looks extremely oppressive — very sleek, cold, monochromatic, and he seems trapped wherever he goes. And it's only when he can get out and breathe the air down on the Lower East Side when he's with Parry that he can actually become a human being and associate more with other humans. Yeah, this is pretty consistent through all my stuff; it springs from the fact that I lived in New York after college for three years. Most of the attitudes I put in my films are based on that period. I find it's a strange place, New York — I mean, all cities are strange, but New York in particular — because it's more of an extreme version of what a city can be. And I'm always torn by them, because on one hand they're this center of incredible activity and energy and massed humanity and I get a real buzz off of that; but then at the same time it seems to crush people. It reduces people to cogs in the machine or molecules within a system, whatever, and that part just drives me crazy, when individuals get lost to be aspects of the machinery. I remember my first view of New York was getting out of the subway at 42nd Street, coming from the airport, and that was just Whooah! There you are at the bottom of these monoliths and there is this dichotomy because it's exhilarating and terrifying at the same time, and so I try to deal with that. That dichotomy is represented by Jack, who's really a product of the times, because he can be both exhilarating and terrifying to listen to on the radio. I made Jack the product of magazines like Metropolis — oops! His world is all about design and it is very photogenic, everything is minimalist. It's reduced to the bare bones. And everything he's in is a cage of one sort or another. He's isolated from the world totally, by all these man-made things. So we've got his radio studio, there are no windows, that's one box he'd be in. We actually put all those little shadows around to make it look like a cage. And he's on his own, he's not even in direct communication with his crew, who are on the other side of this glass barrier. And his only contact with the world is through machines, the telephone — it's nothing that's direct; everything is distanced and made safe in a sense that he doesn't have to get dirty, he doesn't have to rub shoulders. He's in his agent's limo and the world is knocking at his window and he won't open the window. And it's one-way glass; the world can't even see in to him. Yeah, that's right. And then there's his apartment, which again we made a bit cage-like. The apartment is actually based on the Metropolitan Tower which is on 57th Street next to Carnegie Hall, which we used for the outside. I looked up and said, That's where I want Jack to live, the point where the razor-edge wedge slopes back, and it turned out that apartment is owned by Mike Ovitz, whose agency [CAA] I just joined. A very bizarre moment! I mean, I gave Jack all the best clothes; everything he's got is the best the modern material world offers. But there's a tendency for it to lead to isolation, losing touch with anything natural or God-made as opposed to man-made. It's a barren environment he lives in; he's a prisoner of his desire for success. It's the kind of success that I'm afraid love of the modern world aspires to, and in a sense encourages. It's like all those stylish magazines where people pose in the best clothes and the sleekest environments; there's nothing alive in there. There's nothing; everything is very anal, it's all controlled. Jack's controlled his life — he thinks — but by controlling it he's allowed nothing to get into it. And it becomes a very empty life. So that's what all that was: pretty obvious stuff! The locations chosen, such as the Armory at Hunter College or beneath the Manhattan Bridge where Jack meets Parry and the other bums, and the way they're photographed, certainly don't look the way you generally see New York in movies. Yeah, you normally see New York through Woody Allen's eyes, or Rob Reiner trying to be like Woody Allen. I'm amazed because New York is an extraordinary, phenomenally visual city. I always try to use architecture and the sets as a character in the film. I was really doing it like a fairy tale on many levels, when I was designing the thing. So under the Manhattan Bridge when the bums are there, or where Jack's about to commit suicide, it's like the moat of a castle or of a kingdom, the river that surrounds it. And these bridges come from foreign lands and cross into this very restrictive kingdom where everything is thrust together. Jack's living in the great castle with all the money and power the world offers. And then when he falls from grace, the first place he falls is to Anne's video shop, [which is] like the peasant cottage in the forest. That's the way I've always seen the thing. And Anne's very earthy; her tastes are pretty eclectic and awful really, but [her home's] full of life and color and mess, clutter. And she's a live creature there, a love of flesh and blood. And then they go even further down — that's just ground level — then we sort of go below ground level, under things. Under bridges, in the basement with Parry, where it gets really ripe and smelly. A potentially rich ground. I mean, there's a lot of manure down there, a lot of fertilizer for seeds of life. And what I liked about under the bridge was those arches, it's like Piranesi. It's the closest I could come to Piranesi in New York — these very massive classical arches, buttresses, and I quite like that. It's like moving back in history to an earlier time which is now where the homeless and bums live. They live in this, well, literally they're living in a Piranesi world, as opposed to the modern world. Parry certainly fits right in, because he is of that world. He happens to be sort of fixed in the Middle Ages. I was being very broad about where there was new and there was old. And Parry has in part invented this older world which is medieval, and that's why I liked Carmichael's [the millionaire's home which Parry believe houses the Holy Grail], which was originally just a townhouse. I found this armory up on Madison Avenue and 94th Street and it was a medieval castle. If you've got the eyes to see, New York can be anything you want it to be. It can be any world, any time, and Parry has chosen an ancient world, and he's peopled it with castles and princesses. Lydia's office building, I put her in the Metropolitan Life building. It's a Deco building, a great stone building as opposed to a modern building which is steel and glass, because a stone building seemed more like a tower that a princess might be held captive in. And it's really heavily fortified that way — it's got great thick walls, huge blocks of stone. And a revolving door that she can't pass through safely. Then you've got this modern problem that adds to it. I mean, I never try to be a purist about anything. Then the next time we get back to something modern is when Jack's going into the TV executive's office, and we're back into the sleek glass and hard edges. There's a lot just to do with texture — there are things that are smooth and there are things that are rough, and I like things that are rougher because there's a little more chance for things to cling to him. What did production designer Mel Bourne bring to the film? I wanted Mel because he is very experienced in New York [his credits include several Woody Allen pictures and REVERSAL OF FORTUNE], and I wanted somebody who would constantly double-check my choices so that I wasn't forcing too many foreign ideas upon New York. I really felt FISHER KING had to feel real; I didn't want it to turn into my normal `Escape from Reality' designs. So everything had to be a real place, especially on interiors and things which we built. I wanted Mel to be able to choose with the kind of security that you have when you've spent your whole life in New York. Because I didn't trust mine; I haven't been in the States enough over the years to really know all the details of what some of these places were going to be like. What are your plans after FISHER KING? Richard LaGravanese and I are working on a thing called THE DEFECTIVE DETECTIVE. I think it's a nice idea. I keep thinking it's kind of like BRAZIL meets TIME BANDITS — with a little bit of FISHER KING thrown in. And maybe BARON MUNCHAUSEN. I keep doing the same kind of things, I keep rolling... It's a sign of accretion! Yeah, well, that's it, I mean, none of these things are big leaps; every time I think I'm making a big leap I realize I haven't; I've only just gone around the corner a bit. But it's like building one century's architecture on top of another's. Oh it is, it's exactly that. It all starts from one sort of personality disorder and keeps growing.

Previously published in Metropolis Magazine, September 1991.

| |||||||||||||||

copyright 1991, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

One of Gilliam's talents in constructing cities is his agility at finding sources or references in other artists' works and incorporating them into his own. In his early animations, his creative pilferings were quite literal:

bits and pieces of paintings, statues and photographs performed strangely

accentuated comic routines — the hallucinations of a museumgoer on acid.

He feeds upon the contributions of his collaborators — writers,

cameramen, designers, actors — until he hits upon the truth of a situation,

how a particular setting should be in relation to its inhabitants. This was

most successfully done in BRAZIL, set in what the director described as "the

flip side of now," a totalitarian society whose entire apparatus crushes

its citizens in so many ways, leaving flights of fantasy as the only means

of escape.

One of Gilliam's talents in constructing cities is his agility at finding sources or references in other artists' works and incorporating them into his own. In his early animations, his creative pilferings were quite literal:

bits and pieces of paintings, statues and photographs performed strangely

accentuated comic routines — the hallucinations of a museumgoer on acid.

He feeds upon the contributions of his collaborators — writers,

cameramen, designers, actors — until he hits upon the truth of a situation,

how a particular setting should be in relation to its inhabitants. This was

most successfully done in BRAZIL, set in what the director described as "the

flip side of now," a totalitarian society whose entire apparatus crushes

its citizens in so many ways, leaving flights of fantasy as the only means

of escape.