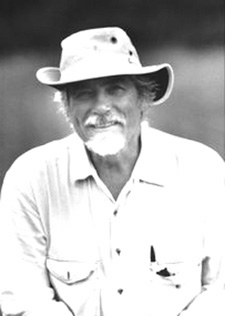

DIRECTORS // Carroll Ballard |

Interview with Director |  |

|

A documentary filmmaker (he received an Oscar nomination for the 1967 feature HARVEST) and veteran of TV commercials, Carroll Ballard made an auspicious Hollywood feature debut with his 1979 feature THE BLACK STALLION, a beautiful telling of Walter Farley's tale. His second feature, which avoided the sophomore jinx, was the 1983 NEVER CRY WOLF, a rare Disney live-action film that suited all ages in its recounting of Farley Mowat's study of wolves in the Arctic. Unfortunately, it was nearly a decade before Ballard's next major feature, WIND, a fictionalized story based on Dennis Conner's victory in the America's Cup yachting race. As we met on WIND's Newport, Rhode Island location in the Spring of 1991, I found Ballard to be of two minds about the project, which was about halfway through production. Having already shot much of the water sequences in Australia (some of which would be re-shot off Hawaii), Ballard was in the throes of shooting the film's dramatic and romantic scenes. While characterization was not necessarily the strongest point of his films in the past, he found it especially hard here to get a grip on what the scenes needed given that the script was in a constant state of re-write, to emphasize the film's romantic elements rather than the yacht race itself. As it turned out, some of the scenes involving Matthew Modine, Jessica Gray and Rebecca Miller evoke a goofy, innocent charm, making their characters rather winning despite the film's split between being a small love story and an epic adventure on the high seas. That Ballard managed to succeed in this regard is (like his characters) a testament to his ability to survive extreme conditions.

Morgan: I admired how in your previous films you treated the environment almost as a character — the desert island in THE BLACK STALLION and the Arctic in NEVER CRY WOLF— and I'm interested with how you are dealing with water, the wide expanses of ocean, as a character because it is an antagonist to the sailors in this story.

This picture has taken a lot of time but the time is mainly devoted to the mechanics of sailing and of getting the boats and the guys out on the water and getting the wind blowing enough to make it interesting, and then the thing with all the characters, a story that takes place on two different continents and all of that, the size of this production is so huge that you know we're not going to have time to do that kind of thing. That's my personal frustration on the film. What is the biggest challenge for you on this? Well it's kind of new ground for me, in the sense that it's not just photography, it's about characters, and motivation, and interreactions. And it's very much an ensemble piece, lot of different characters, two different triangles going on at once, you know, power and glory and all of that stuff, big egos. In a way racing on these big boats is a little bit like making a movie. It's very hard to get it off the ground, it takes so much money, you have to deal with so many people who are not necessarily going to be involved in the actual sailing of the boat, you've got to deal with the scientific guys, the money guys, the technology guys, the rumors, it's this whole big giant thing and it all has to work in order for a boat to be really competitive. And the crew, they've all got to be singing the same song at the same pitch or you got a disaster. To me there's lot of nuances between putting together a sail boat and keeping the thing together during the course of the race, as it is to making a movie. You have to make a lot of the same compromises. The difficulties are much greater than just dealing with sailing a boat — sailing the boat is sort of the least of it. Once you've gotten out on the water. Yeah, it's the logistics and the psychological dynamics and all of those things, insurance, agents' fees, aaaaallllllll the stuff you have to deal with explodes into the horror of the thing. In a way the Matthew Modine character is a guy that comes out very naively, sort of the way I came onto films, that all you need is a camera and you get out there and you shoot it — you know, you get some guys, use the real small crew and you do films real reasonably and you make personal stories, it would be great. That's sort of how I came out of film school, thinking it would be possible, but it isn't possible; it's totally impossible. Essentially you've got to start with a successful con game to raise the money, and to get somebody sold on the project you've got to put together a package, and in order to do that you have to deal with a hundred different people who all have their own self interests involved — agents and the lawyers and the studio people, preparation people, dah de dah de dah. Making the movie is the least of it. And even when you get out there you've got to deal with the Teamsters and the fact that the lunch isn't served on time and a billion other things that you can't possibly imagine. Making a movie oftentimes takes a back seat to just moving the army from here to there. From Australia to here, then to Hawaii. Yeah, I'm just not suited to this process. I'm just not. How did you get involved with this project? Well, the guy showed up on my doorstep about two, three years ago, Mata Yamamoto (the producer of MISHIMA: A LIFE IN FOUR CHAPTERS) and asked me if I would be interested in doing a film about the Americas Cup, about big time sail boats. And I said yes. After all I'd spent 10 years trying to get pictures off the ground; I've seen 14 different projects bite the dust because I couldn't get the funding. So I felt that, yeah you could make an interesting film on it, with interesting visuals and interesting characters, interesting dynamics, but I felt it would be unlikely that he could raise money to do it because it was not a mainline, commercially hot subject to make a film about. And to raise the money I felt would be very difficult, and it would take a lot of money because of the logistics, and the shooting of the picture would be enormously difficult. And so he listened to what I had to say and he left and I totally forgot about it. And a year later he called me up and said, 'Look, I got the money, come on and make this film.' So I go, 'Okay, great, let's make the film,' but we didn't really have the story, we only knew that he had sold this idea based on the Americas Cup — apparently there's a lot of interest in Japan with the Americas Cup because Japan was turning into a very serious competitor for the cup for a couple of years — so we had to invent a story. He initially bought the Dennis Conner story, a book called "Comeback," but I wanted to shy away from doing a film about real history because we didn't want to offend people who had busted their ass to do something by coming out with some ersatz version of their story. I felt it would be better to fictionalize the story set against that background and to draw from a lot of different characters who have been involved through the years. And so we began a long process of trying to write a story and get a script together. We kind of got a story together, it has a shape; to get it on the page we went through several writers and a long torturous process to get to a story that kind of held water. The release date on the picture has to be next spring, so there came a point where we had to say, well, we're going to take this and make a movie out of it one way or another, or we're just going to stop and give up. Mata is a man with a great deal of perseverance and courage on a scale that is unknown in the American film business today, and he went for it, and put his ass a long ways out on the precipice to see this film go into production. So we started in Australia when the script was still trying to keep it up to speed, we were literally writing the film just in front of the cameras in some scenes. And we're still doing that today. The scene that we're doing today did not exist in the form that we're doing it ten hours ago. Which to my way of thinking is a very viable way of making a picture. It's not all that dissimilar to going out with a documentary film crew to see what happens in front of a camera and capturing it. Well, some of the great films in history had been made this way, CASABLANCA was made this way, GONE WITH THE WIND was made this way! GONE WITH THE WIND, they were running in front of the railroad train all the way. And it's totally impossible as far as the American film industry today is concerned; they want to have a product that's prepackaged, pre-sold, predigested and everything before they [give] a permit to do it. So this kind of process used to happen occasionally when people really believed in a project and went out there to do it, but today it is in my experience largely unknown in the American movie industry. It does happen [occasionally]; I think DANCES WITH WOLVES was such a project, it was a project that got off the ground because Costner was a hot guy and somebody was willing to go out on a limb a little bit because, you know, he was Mr. Box Office, he'd done a couple of big films and so he got the money and they kind of left him alone, he went out there to do his movie. Who in the hell would have dreamed that a two-and-a-half hour Indian movie was going to do business? Nobody. And so it's true that good films often do happen like this, but unfortunately it's usually the exception rather than the rule. I feel very bitter about the American corporate film world because I think it's totally unimaginative, completely without spontaneity and I think it takes somebody from outside to improve it. Whether the movie comes out or not, who knows? You know, it may be a total disaster and we all live in disrepute the rest of our lives. At least we're taking a roll, it's a very, very big, big gamble. You don't have the hottest box office people involved, you don't have a story that's hot stuff — we're not making Desert Storm or any of the obvious commercial things that you know the factories are cranking out now. But it is often the less obvious that gets the media attention because it's different. Sometimes it does, yeah. My feeling about this film is that it's either going to be one of the most embarrassing disasters in history or it's going to be a good film, and at this point I really couldn't tell you. I'm curious how you are responding to the technical challenges that face you during shooting. Yeah, I have a really good group of people, a really superb group of people I'm working with, we're doing it as well as we can in the time. John Toll has worked with you on commercials before. Any others with whom you'd worked before? No, I hadn't. Twelve years since I made a picture. How has it been forging working relationships with the crew, given the strenuous working conditions? Very lucky so far, the system's worked, [though it's] an exceedingly difficult picture in terms of not being able to plan it clearly day to day. What has been the happiest surprise for you? There are happy surprises all the time, for me that's the wonderful part of filmmaking; the best part is you go out thinking you're going to do this on a given day, and something happens that's ten times better than what you've dreamed of, and you take advantage of that. As a filmmaker I respond very much more to the stuff that's right there in front of the camera, the potentialities that are there at any given moment.

During our conversation I observed as some of the staff brought in a tape of stock footage — slow motion studies of bees in flight, which might be used to explain the aerodynamics of the yacht's sails. There was also some second-unit footage, shot in a mountainous desert region, which was a possibility for the opening title sequence — a long, slow camera pan, looking up at the craggy, wind-blown buttes. It spoke of timelessness and the inscrutable face of Nature, and yet evoked a haunting ache on the part of the viewer to connect to the natural world. [As it happened, the opening titles of WIND played out, ironically, underwater, with the camera pointed straight up as the hull of a yacht serenely parted the surface. It was vaguely abstract, nicely alluded to forces beyond the understanding of those residing in the sea, and incidentally served up an important plot point in Matthew Modine's character's obsession with designing new and improved boat hulls.] As the afternoon wore on, minor crises erupted on the set. The weather was failing to cooperate, as heavy dark clouds rolled in, allowing for only pinpricks of sunlight here and there. An indoor scene was shot at a home overlooking the rocky shoreline of Newport. As it so happened, the scene featured a partially-nude Rebecca Miller, and while the "unnecessary" crew was barred from the set, the young son of the house's owner got a good glimpse of the actress's breasts through a window. That set off a tumultuous few moments in which the homeowner (evidently unaware that a nude! scene was being shot in her house) threatened to throw the entire crew out onto the street. As daylight faded, Modine and Miller were riding along the cliffs atop a horse, with the crew gently leading the horse away from the cliff's edge. At one point Ballard grabbed a camera and trained its lens on the horse and stars himself — it seemed to speak of a desire to get something on film, to not let Nature have Her way.

Postscript: Finally released in the fall of 1992, WIND failed to reap more than mixed reviews, and it did not find an audience despite the film's visual sweep. Ballard's follow-up, FLY AWAY HOME, about a young girl's efforts to aid the migration of geese, fared much better than WIND, both critically and at the box office. |

copyright 1991, 1997, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

Ballard: There's no room for that in this production. No room for that stuff. It's so expensive there's no place to do natural elements. I originally thought of this as having a lot of those qualities and that personally is my, partially, my interest in making the film. It's just the nature of how this particular production has grown; I don't expect to see a lot of that in this film. It's mainly all-out scenes between characters, a more emotional arc and more a straightforward picture than the last two that I did, because we have an enormous crew, gigantic crew. You can only make a film like that section on the island in THE BLACK STALLION when you're fortunate to go there and spend a lot of time with a small crew; it takes a lot of time to do that.

Ballard: There's no room for that in this production. No room for that stuff. It's so expensive there's no place to do natural elements. I originally thought of this as having a lot of those qualities and that personally is my, partially, my interest in making the film. It's just the nature of how this particular production has grown; I don't expect to see a lot of that in this film. It's mainly all-out scenes between characters, a more emotional arc and more a straightforward picture than the last two that I did, because we have an enormous crew, gigantic crew. You can only make a film like that section on the island in THE BLACK STALLION when you're fortunate to go there and spend a lot of time with a small crew; it takes a lot of time to do that.